I've been thinking lately about feminism in fairy tale retellings, especially since I just wrote a guest post for Spinning Straw Into Gold on the subject of feminism in Beauty and the Beast, and how I think later generations will look back on this era of fairy tale history and roll their eyes and wonder why we were so obsessed with seeing everything as a sermon on gender roles and missing out on the other ways to read into fairy tales. Megan Reichelt of The Dark Forest summed up my feelings precisely in a recent post:

"Modern interpretations have a faux-feminism, saying that all you have to do to

empower women is have them swing a sword around. (See The

Empowerment of Snow White). Should women have to "become masculine" to have

power. Is wielding a sword (or fighting in general) masculine? Personally, I

think if you have a weak female character whose only empowerment is having a

sword, then yes, it is a sham. However, if the character herself is strong, no

matter what she does, sword or knitting, she will be empowered."

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Saturday, November 24, 2012

Thoughts on Rapunzel

This is the campanula rapunculus plant, also known as Rapunzel, or Rampion, and the source of the title of the famous Grimm fairy tale. Rapunzel's birth mother has cravings for various forms of leafy greens in the different versions of the tale, like lettuce or parsley.

Fun fact about the fairy tale from the annotations of Maria Tatar: the Mother Gothel character was originally called a "fairy" in the Grimm story, and later changed to "enchantress." Some English translations use the word "witch." I wrote not too long ago about how Rumpelstiltskin has gradually come to be perceived as more villainous, through changes made to the story's wording and largely due to illustrator's ideas as well. So often fairy tales are thought of as being completely black and white, with characters separated into all good and all evil, but maybe even this is not innate to the nature of fairy tales, but a more recent phenomenon. The narration of the tale never condemns Mother Gothel for wanting to raise a baby as her own child, or wanting to protect her from the world, however extreme her actions may have been. Although she sends a pregnant Rapunzel to fend for herself alone and blinds the prince, Mother Gothel is never punished as many fairy tale witches are-the reader never learns what happens to her.

Fun fact about the fairy tale from the annotations of Maria Tatar: the Mother Gothel character was originally called a "fairy" in the Grimm story, and later changed to "enchantress." Some English translations use the word "witch." I wrote not too long ago about how Rumpelstiltskin has gradually come to be perceived as more villainous, through changes made to the story's wording and largely due to illustrator's ideas as well. So often fairy tales are thought of as being completely black and white, with characters separated into all good and all evil, but maybe even this is not innate to the nature of fairy tales, but a more recent phenomenon. The narration of the tale never condemns Mother Gothel for wanting to raise a baby as her own child, or wanting to protect her from the world, however extreme her actions may have been. Although she sends a pregnant Rapunzel to fend for herself alone and blinds the prince, Mother Gothel is never punished as many fairy tale witches are-the reader never learns what happens to her.

Most illustrations of Rapunzel revolve more around the fantastic length of golden hair, or feature Rapunzel and her lover, but these illustrations by Anne Anderson (above) and Arthur Rackham (below) portray the adoptive mother as a more stereotypical witch.

Another fun fact: Rapunzel's hair is 20 ells long in the Grimm story. Measurements for an ell varied from country to country but was at least 18 inches. So, Rapunzel's hair was at the very least 30 feet long. The French ell was 54 inches, so by that standard her hair would have been 90 feet! My nerdy fascination with numbers aside, the point was not exactly how long it was, but to create a vivid and extreme picture of an unprecedented length of hair.

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

The Glass Coffin

Snow White isn't the only fairy tale character who finds herself in a glass coffin! Enjoy this little known treasure from the Grimms' collection:

"Let no one ever say that a poor tailor cannot do great things and win high honors; all that is needed is that he should go to the right smithy, and what is of most consequence, that he should have good luck." A tailor's apprentice went traveling, and during the night was lost in a forest. To protect himself from wild animals, he resolved to spend the night in a tree, but the wind was great and the tailor was not without fear.

After some hours, he noticed a light in the distance, and went towards it to find shelter and a friendly face. He found a small hut and knocked on the door. The owner of the hut told him to go away, but the tailor was persistent and the owner was not so hard hearted as he wished to appear, so he allowed the tailor to spend the night-he gave him food and a bed.

In the morning, the tailor was awoken by violent screams. Being courageous, he got up and hurried out. He found a stag and a bull engaged in struggle, shaking the ground with their trampling and their cries resounding in the air. The tailor watched as the stag bested the bull, and then caught him up in its horns and carried him swiftly through mountains and valleys, woods and meadows, and at last came to a wall of rock, where he let the tailor down. The stag pushed its horns against a door in the rock, which burst open in a shower of flames and smoke. When the smoke cleared, the tailor was alone in front of the entrance to the rock.

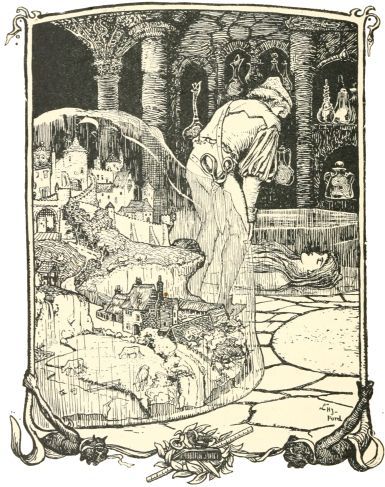

The tailor was uneasy, but a voice came out of the rock, saying, "Enter without fear, no evil shall befall thee." Though still hesitant, the tailor entered the door, driven by a mysterious force, and found himself in a spacious hall. The ceilings and walls had strange letters cut into them. He heard a voice telling him to step on the stone in the middle of the hall, and he obeyed. He found himself in a hall filled with glass vases that contained bluish vapor. There was a glass chest that contained a perfect and detailed miniature of a castle, surrounded by stables and barns.

But the bull that the tailor saw the stag vanquish was none other than the magician himself. Together, the tailor and the maiden placed the castle on a broad stone, where it expanded to its true size. The people were restored, including the maiden's brother, and the maiden and the tailor were married.

*********

I feel like I say this all the time, but here is yet another excellent example: canonized fairy tales have been accused of promoting negative stereotypes of genders, such as women being praised for being mindlessly obedient, whereas men tend to be rewarded for their curiosity. And while this is true in many well-known tales-think of Little Red Riding Hood, Bluebeard's wife, and Psyche, as opposed to Jack the giant-killer-but there are many examples in the larger world of folklore where these stereotypes are NOT enforced.

In this tale, with its wonderful fantastic images, the male protagonist is rewarded for his obedience. Although the woman is helpless for a time in the glass coffin, I don't think she comes across as being weak at all. She has the good sense to be mistrustful of the magician, refuses him marriage twice, and even has the guts to shoot at him! All the tailor really does is open the bolt on the coffin, and it is the maiden who fills him in on the situation, and together they restore her castle. (I feel like in other versions of this story she must be a princess, why else would she have a castle and the people referred to as "her people"?)

Illustrations by HJ Ford.

"Let no one ever say that a poor tailor cannot do great things and win high honors; all that is needed is that he should go to the right smithy, and what is of most consequence, that he should have good luck." A tailor's apprentice went traveling, and during the night was lost in a forest. To protect himself from wild animals, he resolved to spend the night in a tree, but the wind was great and the tailor was not without fear.

After some hours, he noticed a light in the distance, and went towards it to find shelter and a friendly face. He found a small hut and knocked on the door. The owner of the hut told him to go away, but the tailor was persistent and the owner was not so hard hearted as he wished to appear, so he allowed the tailor to spend the night-he gave him food and a bed.

In the morning, the tailor was awoken by violent screams. Being courageous, he got up and hurried out. He found a stag and a bull engaged in struggle, shaking the ground with their trampling and their cries resounding in the air. The tailor watched as the stag bested the bull, and then caught him up in its horns and carried him swiftly through mountains and valleys, woods and meadows, and at last came to a wall of rock, where he let the tailor down. The stag pushed its horns against a door in the rock, which burst open in a shower of flames and smoke. When the smoke cleared, the tailor was alone in front of the entrance to the rock.

The tailor was uneasy, but a voice came out of the rock, saying, "Enter without fear, no evil shall befall thee." Though still hesitant, the tailor entered the door, driven by a mysterious force, and found himself in a spacious hall. The ceilings and walls had strange letters cut into them. He heard a voice telling him to step on the stone in the middle of the hall, and he obeyed. He found himself in a hall filled with glass vases that contained bluish vapor. There was a glass chest that contained a perfect and detailed miniature of a castle, surrounded by stables and barns.

On the other end of the room was another glass case, but it contained a maiden of greatest beauty, sleeping. The maiden suddenly opened her eyes and said, "My deliverance is at hand!" She instructed the tailor to push back the bolt of the coffin and free her. Once he did this, the woman told him her story.

The maiden was the daughter of a count, who lived with her brother in harmony with him and the rest of the world. One day a strange man came to their house and they showed him hospitality. In the middle of the night, the woman was awoken by the sound of strange music. She meant to call for her maid, but found she could not speak. The strange man entered the room and explained that he had summoned the music by magical arts, and intended for her to be his wife. The woman refused, and this angered the stranger. In the morning she awoke to find that the man had turned her brother into a stag. The woman tried to shoot the man, but the bullet bounced back and hit her horse.

The magician had shrunken her castle, and imprisoned her people into vapors. He promised to return everything to its original state if she would now consent to marry him, but again she refused. The magician confined her in a glass coffin and caused a deep sleep to come upon her.But the bull that the tailor saw the stag vanquish was none other than the magician himself. Together, the tailor and the maiden placed the castle on a broad stone, where it expanded to its true size. The people were restored, including the maiden's brother, and the maiden and the tailor were married.

*********

I feel like I say this all the time, but here is yet another excellent example: canonized fairy tales have been accused of promoting negative stereotypes of genders, such as women being praised for being mindlessly obedient, whereas men tend to be rewarded for their curiosity. And while this is true in many well-known tales-think of Little Red Riding Hood, Bluebeard's wife, and Psyche, as opposed to Jack the giant-killer-but there are many examples in the larger world of folklore where these stereotypes are NOT enforced.

In this tale, with its wonderful fantastic images, the male protagonist is rewarded for his obedience. Although the woman is helpless for a time in the glass coffin, I don't think she comes across as being weak at all. She has the good sense to be mistrustful of the magician, refuses him marriage twice, and even has the guts to shoot at him! All the tailor really does is open the bolt on the coffin, and it is the maiden who fills him in on the situation, and together they restore her castle. (I feel like in other versions of this story she must be a princess, why else would she have a castle and the people referred to as "her people"?)

Illustrations by HJ Ford.

Friday, November 16, 2012

More Thoughts on Princess and the Pea

Some readers find it upsetting that the princess of The Princess and the Pea is valued according to shallow standards of wealth, which in the fairy tale crosses over to a ridiculous test of "true" princesshood. Maria Tatar suggests that "the sensitivity of the princess can also be read on a metaphorical level as a measure of the depth of her feeling and compassion."

When I first read that, my reaction was, "eh, that's a stretch," but on further reading of the tale I totally agree. I must admit this is one of the tales I haven't read in a while (if ever...? It's not in my collection of Andersen tales for some reason) and assume I know enough just from being familiar with the plot. Many people tend to make assumptions based on familiar plot points without actually reading the full stories, which can often surprise you...

1. "He went in search of a princess of his own, but he wanted her to be a true princess. And so, he traveled all over the world in order to find one, but something was always wrong."

If by "true princess" the prince just meant a girl born to a king and a queen, it should not have been that hard for him to find one in his travels around the world. This stipulation sounds to me more like when adults refer to little girls as princesses, either to increase their self esteem or motivate them towards more noble behavior (like George MacDonald in his introduction to Princess and the Goblin).

2. One evening there was a terrible storm, and "there was a princess standing outside. But goodness gracious! What a sight she was out in the rain in this kind of weather! Water was running down her hair and her clothes. It flowed out through the tips of her shoes and back out again through the heels. And still, she insisted that she was a real princess."

In light of this episode, it's impossible that the meaning of the prince's search could have been for a princess who was accustomed only to luxury. That kind of princess would have arrived at the palace in a magnificent carriage, surrounded by attendants. This princess arrived at the castle-on foot, alone, and in the rain, and apparently uncomplaining about it! As Tatar points out as well, the princess did not sit at home and wait to be found, but actively sought out this prince.

The famous rest of the fairy tale, with the pea and twenty mattresses, is probably meant to be humorous and whimsical. The pea itself goes on to fame, on display a museum, "where it is still on display, unless someone has stolen it.

There. That's something of a story, isn't it?"

Illustrations by Kay Nielsen

When I first read that, my reaction was, "eh, that's a stretch," but on further reading of the tale I totally agree. I must admit this is one of the tales I haven't read in a while (if ever...? It's not in my collection of Andersen tales for some reason) and assume I know enough just from being familiar with the plot. Many people tend to make assumptions based on familiar plot points without actually reading the full stories, which can often surprise you...

1. "He went in search of a princess of his own, but he wanted her to be a true princess. And so, he traveled all over the world in order to find one, but something was always wrong."

If by "true princess" the prince just meant a girl born to a king and a queen, it should not have been that hard for him to find one in his travels around the world. This stipulation sounds to me more like when adults refer to little girls as princesses, either to increase their self esteem or motivate them towards more noble behavior (like George MacDonald in his introduction to Princess and the Goblin).

2. One evening there was a terrible storm, and "there was a princess standing outside. But goodness gracious! What a sight she was out in the rain in this kind of weather! Water was running down her hair and her clothes. It flowed out through the tips of her shoes and back out again through the heels. And still, she insisted that she was a real princess."

In light of this episode, it's impossible that the meaning of the prince's search could have been for a princess who was accustomed only to luxury. That kind of princess would have arrived at the palace in a magnificent carriage, surrounded by attendants. This princess arrived at the castle-on foot, alone, and in the rain, and apparently uncomplaining about it! As Tatar points out as well, the princess did not sit at home and wait to be found, but actively sought out this prince.

The famous rest of the fairy tale, with the pea and twenty mattresses, is probably meant to be humorous and whimsical. The pea itself goes on to fame, on display a museum, "where it is still on display, unless someone has stolen it.

There. That's something of a story, isn't it?"

Illustrations by Kay Nielsen

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

"Fairy tales were not my escape from reality as a child; rather, they were my reality -- for mine was a world in which good and evil were not abstract concepts, and like fairy-tale heroines, no magic would save me unless I had the wit and heart and courage to use it widely."

~Terri Windling~

"Surviving Childhood"

The Armless Maiden

1995

"Surviving Childhood"

The Armless Maiden

1995

Quote found on Surlalune's Fairy Tale Quotes page-check it out if you haven't already! Illustration of Beauty and the Beast by Angela Barrett

Saturday, November 10, 2012

Marina Warner: Silence of Women in Fairy Tales

Fairy tales are often accused of portraying negative female stereotypes, encouraging young girls to become passive and silent and obedient to men.

In one sense this is true-when men such as the brothers Grimm collected fairy tales, they tended not to include stories which existed in folklore that featured strong, clever female heroines, and instead gravitated (however consciously is debatable) towards stories with active males and passive females. Not only that, but as Marina Warner cites from Ruth Bottigheimer's analysis of speech patterns in the Grimms, as the Grimms published their later editions, the female heroines used less and less words and the female villains spoke more. Thus girls tend to subconsciously receive the message that to be good and desirable like the female heroines in the stories, they must be quiet.

There are two famous examples of females who aren't simply reserved, but are completely unable to speak-Hans Christian Andersen's Little Mermaid, and the sister from The Wild Swans and its variants.

The Little Mermaid stands in direct contrast to the sea maidens of antiquity, the sirens. Sirens used their voices, beautiful and alluring, to draw men to them and cause their death. Their voices are therefore powerful, and evil. The Little Mermaid gives up her voice willingly for the chance to win the love of a prince and her immortal soul. Now the desire is hers, but it is she who is forsaken.

The Disney version makes Ariel, in Warner's words, "a fairytale heroine of our time." She knows what she wants (another word count fun fact-the word "want" is spoken by Ariel more than any other verb) and will go through anything to get it, but this time hers is a happy ending. But in this version, according to Warner, "female eloquence, the siren's song, is not presented as fatal any longer, unless it rises in the wrong place and is aimed at the wrong target." The female voice is now powerful like the siren's, but not inherantly evil.

The sister in the Wild Swans is silent by choice-if she speaks one word before the shirts of nettles are made and placed on her enchanted brothers, they will stay swans forever. In one sense, this can be seen as yet another example of encouraging women to be quiet and submissive, but I always return to this: though she is rewarded for enduring, the silence is clearly meant as a hardship-the happy ending includes a return of her voice. (In a way, the heroine from Goose Girl is also silenced, because she gave her word not to tell the truth of her situation to a living being-but the characters are able to find a clever way for her to reveal the truth anyway).

Not only that, but silence should not always be interpreted as a bad thing. Don't get me wrong; I don't support the suppressing of voices of any gender. But this is Warner's personal memories of reading the Wild Swans, one of her favorite childhood stories: "it still seemed to me to tell a story of female heroism, generosity, staunchness; I had no brothers, but I fantasized, at night, as I waited to go to sleep, that I had, perhaps even as many tall and handsome youths as the girl in the story, and that I would do something magnificent for them that would make them realize I was one of them, as it were, their equal in courage and determination and grace" (emphasis mine). The actions of the sister are indeed impressive-there are different forms of heroism, not all that are as easy to recognize-but those that are quieter are often the most noble.

Fortunately, we are not as contrained by the severe gender expectations of the Victorian times, but that doesn't mean these stories or even these particular versions have to be thrown out and completely replaced with new "girl power" versions. There are times when we all feel silenced-we don't feel like our opinions are being taken seriously at work, we feel overlooked in a certain relationship-it can be encouraging to read that there will come a time when we will be able to speak again and the truth will be revealed.

Illustrations of Little Mermaid by Margaret Tarrant, Six Swans by Elenore Abbott

Information from Marina Warner's From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and their Tellers

In one sense this is true-when men such as the brothers Grimm collected fairy tales, they tended not to include stories which existed in folklore that featured strong, clever female heroines, and instead gravitated (however consciously is debatable) towards stories with active males and passive females. Not only that, but as Marina Warner cites from Ruth Bottigheimer's analysis of speech patterns in the Grimms, as the Grimms published their later editions, the female heroines used less and less words and the female villains spoke more. Thus girls tend to subconsciously receive the message that to be good and desirable like the female heroines in the stories, they must be quiet.

There are two famous examples of females who aren't simply reserved, but are completely unable to speak-Hans Christian Andersen's Little Mermaid, and the sister from The Wild Swans and its variants.

The Little Mermaid stands in direct contrast to the sea maidens of antiquity, the sirens. Sirens used their voices, beautiful and alluring, to draw men to them and cause their death. Their voices are therefore powerful, and evil. The Little Mermaid gives up her voice willingly for the chance to win the love of a prince and her immortal soul. Now the desire is hers, but it is she who is forsaken.

The Disney version makes Ariel, in Warner's words, "a fairytale heroine of our time." She knows what she wants (another word count fun fact-the word "want" is spoken by Ariel more than any other verb) and will go through anything to get it, but this time hers is a happy ending. But in this version, according to Warner, "female eloquence, the siren's song, is not presented as fatal any longer, unless it rises in the wrong place and is aimed at the wrong target." The female voice is now powerful like the siren's, but not inherantly evil.

The sister in the Wild Swans is silent by choice-if she speaks one word before the shirts of nettles are made and placed on her enchanted brothers, they will stay swans forever. In one sense, this can be seen as yet another example of encouraging women to be quiet and submissive, but I always return to this: though she is rewarded for enduring, the silence is clearly meant as a hardship-the happy ending includes a return of her voice. (In a way, the heroine from Goose Girl is also silenced, because she gave her word not to tell the truth of her situation to a living being-but the characters are able to find a clever way for her to reveal the truth anyway).

Not only that, but silence should not always be interpreted as a bad thing. Don't get me wrong; I don't support the suppressing of voices of any gender. But this is Warner's personal memories of reading the Wild Swans, one of her favorite childhood stories: "it still seemed to me to tell a story of female heroism, generosity, staunchness; I had no brothers, but I fantasized, at night, as I waited to go to sleep, that I had, perhaps even as many tall and handsome youths as the girl in the story, and that I would do something magnificent for them that would make them realize I was one of them, as it were, their equal in courage and determination and grace" (emphasis mine). The actions of the sister are indeed impressive-there are different forms of heroism, not all that are as easy to recognize-but those that are quieter are often the most noble.

Fortunately, we are not as contrained by the severe gender expectations of the Victorian times, but that doesn't mean these stories or even these particular versions have to be thrown out and completely replaced with new "girl power" versions. There are times when we all feel silenced-we don't feel like our opinions are being taken seriously at work, we feel overlooked in a certain relationship-it can be encouraging to read that there will come a time when we will be able to speak again and the truth will be revealed.

Illustrations of Little Mermaid by Margaret Tarrant, Six Swans by Elenore Abbott

Information from Marina Warner's From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and their Tellers

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

Harrod's Fairytale holiday windows

I found these on Kingdom of Style-Harrod's department store in London is featuring Disney princesses reimagined by fashion designers.

Sleeping Beauty-Elie Saab

Snow White-Oscar de la Renta

Which prompted me to search for more pictures: these are found here, where they can be viewed much larger:

Tiana from Princess and the Frog-Ralph and Russo

Ariel-Marchesa

Pocahontas by Roberto Cavalli, Cinderella by Versace, Rapunzel by Jenny Peckham

Tuesday, November 6, 2012

Tim Walker: Story Teller

Carrie of WishWishWish was able to interview Tim Walker on his latest exhibit, Story Teller, supported by Mulberry. My interest was piqued when I read that fairy tales was one of his inspirations, although as it often happens with art and fashion, that translates more into a vague sense of being whimsical rather than specific fairy tale connections.

However, I very much appreciated the above quote, that "fairy tales are very sinister things." It's such a misconception that continues to circulate that fairy tales are simplistic and childish. Of course, anyone reading this probably has a greater appreciation for fairy tales than the average person and I feel like I've talked about this many times before, so I'll leave it at that and let you click through to read more if you're interested.

However, I very much appreciated the above quote, that "fairy tales are very sinister things." It's such a misconception that continues to circulate that fairy tales are simplistic and childish. Of course, anyone reading this probably has a greater appreciation for fairy tales than the average person and I feel like I've talked about this many times before, so I'll leave it at that and let you click through to read more if you're interested.

Sunday, November 4, 2012

The Seal Maiden: A Tale of the Hebrides

"The King of the Sea had a beautiful Queen, and they loved each other dearly. They had delight in many children, who were all straight-limbed, brown-eyed, eager-hearted, and their happiness was greater than any tongue can tell.

Suddenly dark sorrow fell upon this King. His wife tarried too long on the level white sands; a great storm arose before she could reach safety in the pearl palaces of the sea, and she was trampled to death by the wild sea-horses as they rushed and bounded over the grey granite ledges of the isles.

Lonely in his soul and grieving for his children, the King sought the cave of the sea-witch. Thinking she would care for his children, he married her, but when she saw their surpassing loveliness green envy and black hatred surged within her. One night when the moon was hidden behind dark massy clouds, and the sea moaned with its swelling pain, she distilled a magic from the yellow berries of deadly sea-grape that grew on its pale green sickly stem around the entrance of the cave.

This magic enchanted the children of the sea, so that they became seals. But each year for one day and one night, from sun-down to sun-down, they could take and enjoy their own shapes again.

So it chanced that a young fisher-lad toiling in the early dawn saw a sweet maid playing in the white foam, and loved her. All that day long they roamed together among the moon-flowers, hearing the music of the murmuring tide. When evening came they watched the rising moon cast its silver pathway over the lulling sea. Then a little sobbing wind began to creep over the surface of the deep. The maiden grew strange and shy, and presently she slipped away among the black shadows of the great grey rocks on the shimmering sands. Puzzled and angry, the fisher sought for her, but found only at last a lonely seal, whose eyes were brown and kind and loving. They say that madness came upon him. Madle he sailed away in the teeth of a lowering storm. His frail boat was dashed to pieces on the cruel rocks over the cave of the sea-witch, where grow the deadly yellow berries of the sea-grape on its pale sickly stem."

Kisimul Castle, Scotland

Thursday, November 1, 2012

Artist feature: Walter Crane

The Frog Prince

Walter Crane (1845-1915) was an English illustrator of fairy tales who is known for creating picture books known as "toy books." Each book had eight pages, completely full of color and text, with detailed backgrounds that draw the eye to the page and keep them lingering, soaking up all there is to see.

Beauty and the Beast

According to Walter Crane himself, "Children, like the ancient Egyptians, appear to see most things in profile, and like definite statements in design. They prefer well-defined forms and bright, frank color. They don't want to bother about three dimensions."

At sixpence each, Crane's toy books were made affordable and "children's books began to take on the character of an industry." According to Maria Tatar, "His work, which legitimized a turn to children's fare for serious artists, marked a real milestone in the aesthetic quality of children's books."

Little Red Riding Hood

The Sleeping Beauty

Bluebeard

Jack and the Beanstalk