A non-Disney Grimm's fairy tale tea set!

Available through Reutter porcelain

Sunday, April 21, 2013

Friday, April 19, 2013

History of Aladdin

Out of all the tales of the Arabian Nights, only a few are familiar with modern audiences, and out of those the most well-known would undoubtably be "Aladdin". The story was very popular among adults and children of the Victorian age as well as today. Somewhat sadly, though, the reason for this popularity can be boiled down to the fact that those tales are the least authentic.

Arabian Nights (or 1001 Nights) is a collection of anonymous tales, most of which were orally circulated folktales in the Middle East before being published in the collection. Certain stories, however, were most likely written by one of the French collectors and editors of the tales, Antoine Galland. Other stories that were most likely his creations are "Ali Baba" and "Sinbad," some of the few tales in the Nights average people today could actually name off the top of their heads.

These tales have no known precedents before Galland, and also bear characteristics that are closer to Western fairy tales than the other tales in the Nights. Westerners love their stories to feature protagonists of low birth and status, who find themselves part of an undeserved high destiny which includes marrying outside of their status, and ultimately overcoming their poverty. The multiple scenes and locations of Aladdin also make the story entertaining as the plot keeps changing, and therefore also well suited to the stage, where it was a popular story in Victorian times, as the public loved the spectacles of Oriental scenery and the showmanship of the magical stage tricks.

Galland's original Aladdin story was 118 pages long, and Marina Warner calls it "one of the key works in the history of exchange between literature of the East and West." However, Robert Irwin criticizes Galland's version for being too long-winded, "hypocritical French moral didacticism," and anti-Semitic. Irwin approves of the Disney version's changes to the story, (which is an unusual academic perspective when dealing with fairy tale history, to like the Disney movie better than the original)-he said it was "less vulgar than Galland's, less obsessed with opulence, less sexist, and not at all anti-Semitic."

Warner points out one very interesting feature of the story and possibly its popularity: the issue of slavery. Aladdin finds himself in posession of a magical ring and a magical lamp, both of which have several genie slaves which then must serve Aladdin. When she first pointed this out, I was reminded of "Beauty and the Beast", and the role reversals found in each: in "Aladdin", the poor boy suddenly becomes the master of powerful slaves; in "Beauty and the Beast", the poor woman is told by a powerful male Beast that she is the mistress of his castle, upsetting gender and social status. It's not surprising to find this similar theme, which was a popular one of Galland, Villeneuve, and their French salon contemporaries.

However, Warner also points to a connection with abolitionism. For a while, versions of the story ended with the genie slaves being freed and the villain who imprisoned them punished (as is also how the very American Disney film ends). In Warner's words, "The concept of an utterly subjugated, volitionless but powerful spirit communicates the soulless, dehumanised condition of enslavement decried by abolitionists."

*Information taken from Marina Warner's Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights

Image from here

These tales have no known precedents before Galland, and also bear characteristics that are closer to Western fairy tales than the other tales in the Nights. Westerners love their stories to feature protagonists of low birth and status, who find themselves part of an undeserved high destiny which includes marrying outside of their status, and ultimately overcoming their poverty. The multiple scenes and locations of Aladdin also make the story entertaining as the plot keeps changing, and therefore also well suited to the stage, where it was a popular story in Victorian times, as the public loved the spectacles of Oriental scenery and the showmanship of the magical stage tricks.

Image from here

Warner points out one very interesting feature of the story and possibly its popularity: the issue of slavery. Aladdin finds himself in posession of a magical ring and a magical lamp, both of which have several genie slaves which then must serve Aladdin. When she first pointed this out, I was reminded of "Beauty and the Beast", and the role reversals found in each: in "Aladdin", the poor boy suddenly becomes the master of powerful slaves; in "Beauty and the Beast", the poor woman is told by a powerful male Beast that she is the mistress of his castle, upsetting gender and social status. It's not surprising to find this similar theme, which was a popular one of Galland, Villeneuve, and their French salon contemporaries.

Edmund Dulac

However, Warner also points to a connection with abolitionism. For a while, versions of the story ended with the genie slaves being freed and the villain who imprisoned them punished (as is also how the very American Disney film ends). In Warner's words, "The concept of an utterly subjugated, volitionless but powerful spirit communicates the soulless, dehumanised condition of enslavement decried by abolitionists."

*Information taken from Marina Warner's Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

An answer to my own question

So my wonderful Prince Charming was doing some research of his own (he was my "research assistant" at the Library of Congress last month, and an excellent one at that! A huge thank you!) and found an artcle by Virginia E. Swain in The Greenwood Encklopedia of folktales and fairytales that answers the questions I was just asking about the cultural significance of the Beast asking Belle to sleep with him.

"In the original edition, the story is told within a frame narrative, which is usually removed when the fairy tale is anthologized. Within the frame, the audience of Beauty and the Beast is a group of young adults, including a young woman who is about to be married. This accounts for the story's frank references to sex, such as the Beast's repeated inquiry to Beauty: "Do you want to sleep with me?" This brutal question suggests Villeneuve's understanding that women face the constant threat of rape, even in their marriages. Beauty's ability to defer the event offers a rare example for the time of a woman exercising power in her own behalf. Nonetheless, it is debatable whether the novel, with its overriding emphasis on self-sacrifice, is truly a feminist tale."

Emphasis mine. In my opinion, this element of a woman wielding the power of the "no" is a HUGE example of feminism for the time-feminism has to be seen in the context, and even novels and TV shows from 50-150 years ago may seem incredibly sexist to us but were remarkably groundbreaking in their time. In addition, though self-sacrifice has sometimes been seen as a quality only expected in women, I think it's a beautiful quality that should be found in everyone regardless of gender, so I don't think of it as making the story less feminist.

A.L. Bowley

"In the original edition, the story is told within a frame narrative, which is usually removed when the fairy tale is anthologized. Within the frame, the audience of Beauty and the Beast is a group of young adults, including a young woman who is about to be married. This accounts for the story's frank references to sex, such as the Beast's repeated inquiry to Beauty: "Do you want to sleep with me?" This brutal question suggests Villeneuve's understanding that women face the constant threat of rape, even in their marriages. Beauty's ability to defer the event offers a rare example for the time of a woman exercising power in her own behalf. Nonetheless, it is debatable whether the novel, with its overriding emphasis on self-sacrifice, is truly a feminist tale."

Emphasis mine. In my opinion, this element of a woman wielding the power of the "no" is a HUGE example of feminism for the time-feminism has to be seen in the context, and even novels and TV shows from 50-150 years ago may seem incredibly sexist to us but were remarkably groundbreaking in their time. In addition, though self-sacrifice has sometimes been seen as a quality only expected in women, I think it's a beautiful quality that should be found in everyone regardless of gender, so I don't think of it as making the story less feminist.

Saturday, April 13, 2013

Hans Christian Andersen on women and vanity

Hans Christian Andersen is quite an interesting person. He is well known for several very sweet fairy tales, such as "The Ugly Duckling", "Princess and the Pea", and "The Emperor's New Clothes"-as well as some more sad and moving stories, such as "Little Mermaid" (most people are surprised to learn how different his story is from Disney's, although the same applies for pretty much any Disney fairy tale) and "The Little Match Girl".

Slightly less well-known is his tale "The Red Shoes" (which I've blogged about before), which speaks out very vehemently against girls who take too much pride in their appearance. I was surprised to read another lesser known tale recently that possibly speaks even more strongly against vanity, "The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf".

Full text is available through the link above, but basically what happens is: a young girl named Inger is a terrible person who tortures insects for fun and refuses to visit her mother, who is in poverty ("she was pretty, and that was her misfortune"). Finally she allows herself to be convinced to go and visit her mother, and she is sent with loaves of bread to give to her. She comes across some mud, and so she doesn't ruin her shoes, she puts the bread on the ground to walk on them, and ends up sinking into the mud anyway and dying and going to hell.

She was found by a devil's grandmother and turned into a statue and put outside of the devil's house. To make sure we get the lesson, ""That's the fruit of wishing to keep one's feet neat and tidy," she said to herself. "Just look how they're all staring at me!" Yes, certainly, the eyes of all were fixed upon her, and their evil thoughts gleamed forth from their eyes, and they spoke to one another, moving their lips, from which no sound whatever came forth: they were very horrible to behold."

It goes on an on while Inger suffers as a statue and feels remorse as her earthly mother and mistress weep over her and she realizes she should have been punished. Finally her mother grows old and dies, and weeps for her child, and Inger is turned into a bird. Some children see the bird and it flies away.

"Andersen often fell in love with unattainable women and many of his stories are interpreted as references.[18] At one point, he wrote in his diary: "Almighty God, thee only have I; thou steerest my fate, I must give myself up to thee! Give me a livelihood! Give me a bride! My blood wants love, as my heart does!"[19] A girl named Riborg Voigt was the unrequited love of Andersen's youth. A small pouch containing a long letter from Riborg was found on Andersen's chest when he died, several decades after he first fell in love with her, and after he supposedly fell in love with others. Other disappointments in love included Sophie Ørsted, the daughter of the physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, and Louise Collin, the youngest daughter of his benefactor Jonas Collin. The most famous of these was the opera soprano Jenny Lind. One of his stories, The Nightingale, was a written expression of his passion for Lind, and became the inspiration for her nickname, the "Swedish Nightingale". Andersen was often shy around women and had extreme difficulty in proposing to Lind. When Lind was boarding a train to take her to an opera concert, Andersen gave Lind a letter of proposal. Her feelings towards him were not the same; she saw him as a brother, writing to him in 1844 "farewell... God bless and protect my brother is the sincere wish of his affectionate sister, Jenny."[20]

Maria Tatar discusses how Andersen's characters' sufferings differ from other fairy tales in that, while other villains are often forced to undergo grotesque punishments, Andersen seems to delight in making his heroines undergo all sorts of tortures. I don't mind it as much in some tales-to me "Little Match Girl" is like Dickens stories that expose the truth of how children in poverty suffer. But other heroines, like Karen from the Red Shoes, Inger, and even the little Mermaid, undergo extreme pains that are presented as just punishments for their actions.

Tatar quotes John Griffith, who points out that Anderson's main characters are "small, frail, more likely to be female than male-above all, delicate, an embodiment of that innocence which is harmlessness, that purity which is incapacity for lust."

Andersen is a complex man whose writings reveal interesting and sometimes disturbing insights into his mind. I feel like he's the type of person psychologists love to speculate about and write theses on.

Slightly less well-known is his tale "The Red Shoes" (which I've blogged about before), which speaks out very vehemently against girls who take too much pride in their appearance. I was surprised to read another lesser known tale recently that possibly speaks even more strongly against vanity, "The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf".

Jennie Harbor

Full text is available through the link above, but basically what happens is: a young girl named Inger is a terrible person who tortures insects for fun and refuses to visit her mother, who is in poverty ("she was pretty, and that was her misfortune"). Finally she allows herself to be convinced to go and visit her mother, and she is sent with loaves of bread to give to her. She comes across some mud, and so she doesn't ruin her shoes, she puts the bread on the ground to walk on them, and ends up sinking into the mud anyway and dying and going to hell.

She was found by a devil's grandmother and turned into a statue and put outside of the devil's house. To make sure we get the lesson, ""That's the fruit of wishing to keep one's feet neat and tidy," she said to herself. "Just look how they're all staring at me!" Yes, certainly, the eyes of all were fixed upon her, and their evil thoughts gleamed forth from their eyes, and they spoke to one another, moving their lips, from which no sound whatever came forth: they were very horrible to behold."

Oskar Klever

It goes on an on while Inger suffers as a statue and feels remorse as her earthly mother and mistress weep over her and she realizes she should have been punished. Finally her mother grows old and dies, and weeps for her child, and Inger is turned into a bird. Some children see the bird and it flies away.

I figured there had to be something in Andersen's life to cause this near-hatred of vain women, or women he perceives to be vain (you could argue that not wanting to ruin your shoes is more practical than vain). A while back I had attempted to read Andersen's autobiography, which I found to be too long-winded and I got a vibe that he was very full of himself. But wikipedia has some interesting and pertinent information:

Ben Kutcher

"Andersen often fell in love with unattainable women and many of his stories are interpreted as references.[18] At one point, he wrote in his diary: "Almighty God, thee only have I; thou steerest my fate, I must give myself up to thee! Give me a livelihood! Give me a bride! My blood wants love, as my heart does!"[19] A girl named Riborg Voigt was the unrequited love of Andersen's youth. A small pouch containing a long letter from Riborg was found on Andersen's chest when he died, several decades after he first fell in love with her, and after he supposedly fell in love with others. Other disappointments in love included Sophie Ørsted, the daughter of the physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, and Louise Collin, the youngest daughter of his benefactor Jonas Collin. The most famous of these was the opera soprano Jenny Lind. One of his stories, The Nightingale, was a written expression of his passion for Lind, and became the inspiration for her nickname, the "Swedish Nightingale". Andersen was often shy around women and had extreme difficulty in proposing to Lind. When Lind was boarding a train to take her to an opera concert, Andersen gave Lind a letter of proposal. Her feelings towards him were not the same; she saw him as a brother, writing to him in 1844 "farewell... God bless and protect my brother is the sincere wish of his affectionate sister, Jenny."[20]

Just as with his interest in women, Andersen would become attracted to nonreciprocating men. For example, Andersen wrote to Edvard Collin:[21] "I languish for you as for a prettyCalabrian wench... my sentiments for you are those of a woman. The femininity of my nature and our friendship must remain a mystery." Collin, who preferred women, wrote in his own memoir: "I found myself unable to respond to this love, and this caused the author much suffering." Likewise, the infatuations of the author for the Danish dancer Harald Scharff[22] and Carl Alexander, the young hereditary duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach,[23] did not result in any relationships."

Hans Christian Andersen

Being rejected by men and women, it's no wonder Andersen might have tried to find other ways to explain why no one was romantically interested in him-maybe he reasoned that if the women who rejected him were all vain and shallow, then it wasn't due to his own faults.

Maria Tatar discusses how Andersen's characters' sufferings differ from other fairy tales in that, while other villains are often forced to undergo grotesque punishments, Andersen seems to delight in making his heroines undergo all sorts of tortures. I don't mind it as much in some tales-to me "Little Match Girl" is like Dickens stories that expose the truth of how children in poverty suffer. But other heroines, like Karen from the Red Shoes, Inger, and even the little Mermaid, undergo extreme pains that are presented as just punishments for their actions.

Tatar quotes John Griffith, who points out that Anderson's main characters are "small, frail, more likely to be female than male-above all, delicate, an embodiment of that innocence which is harmlessness, that purity which is incapacity for lust."

Andersen is a complex man whose writings reveal interesting and sometimes disturbing insights into his mind. I feel like he's the type of person psychologists love to speculate about and write theses on.

Tuesday, April 9, 2013

Artist Feature: Errol Le Cain

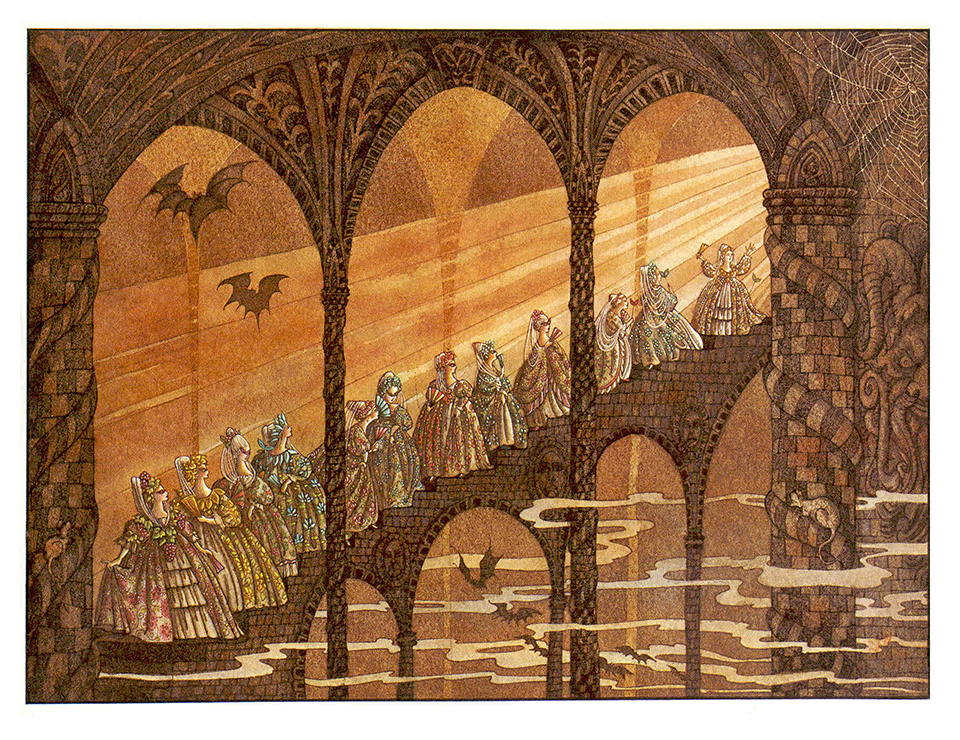

Twelve Dancing Princesses

Molly Whuppie

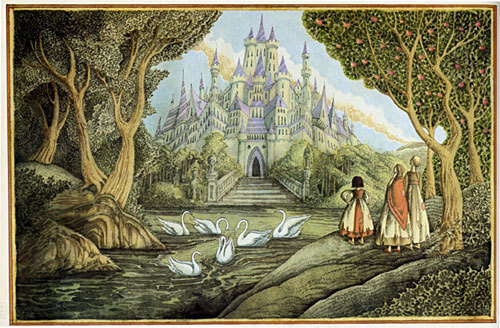

The Enchanter's Daughter

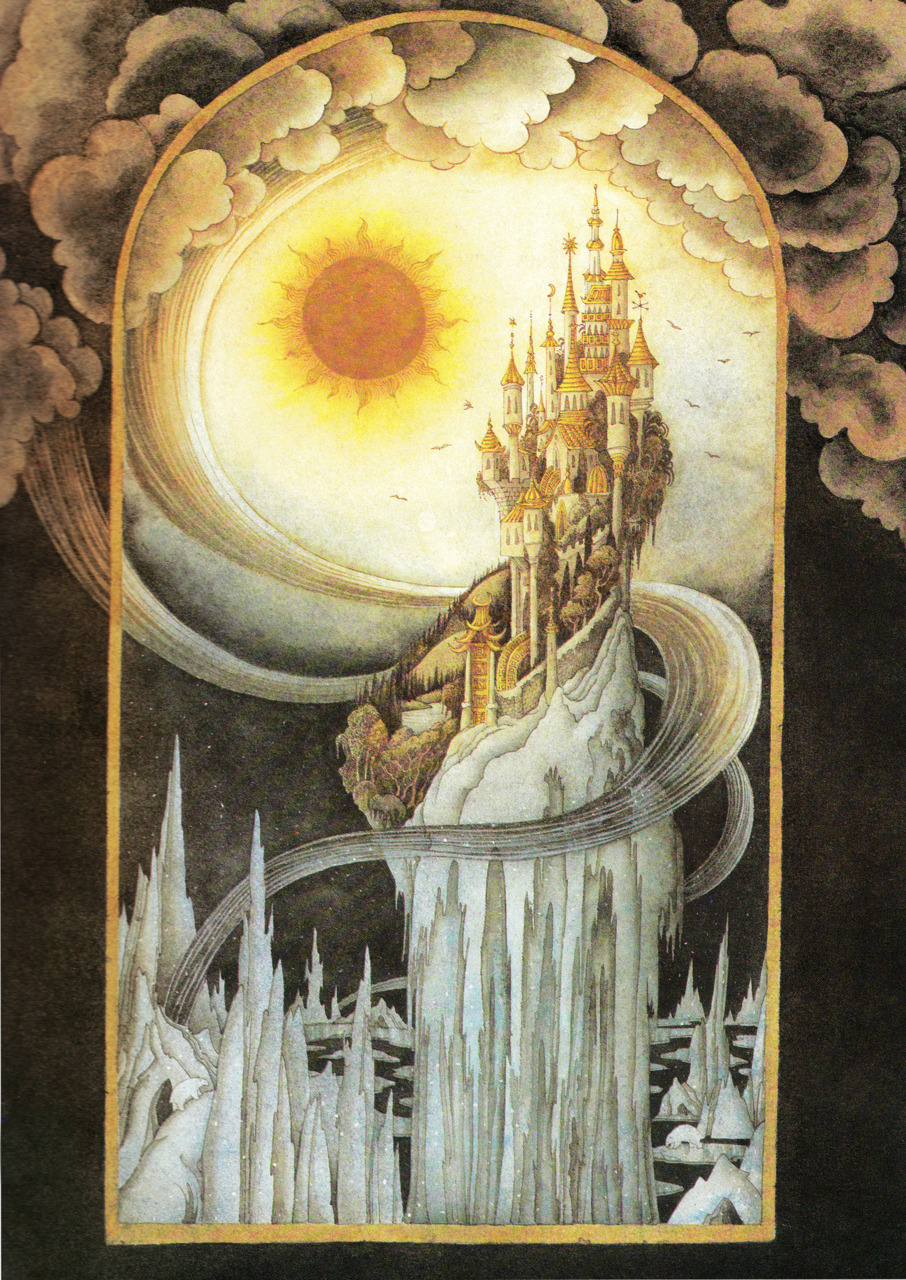

Snow Queen

Cupid and Psyche

Cinderella

There are too many fantastic images to choose from by Errol le Cain (1941-1989), I could have kept going for a while! Alas, I must get to work...

Friday, April 5, 2013

Oh, we like the Disney versions of these much better

"We had a book of Grimm's fairy tales, but they were so dark and violent, as we read them we were like, 'Oh, we like the Disney versions of these much better!'"

There's been much discussion of appropriateness of fairy tales for children in academia and in the blogging world, which I have somewhat contributed to in the past (click on the "children" tag if you're interested in further reading). The parent of two of my students said this the other day, which I found interesting. She has daughters ranging from four to eleven years.

Arthur Rackham-Rapunzel

From here-reference to Grimm's Cinderella

Disney's Rapunzel and Cinderella

Tuesday, April 2, 2013

Villeneuve's Beauty and the Beast: To marry or to sleep with?

One of the main questions I had going into reading the French version of Villeneuve was the issue of what Beast asks Beauty every night. Most of what I had read on the subject talked about how blatantly sexual the Villeneuve version was, and how the Beast asks to sleep with her every night, but the Jack Zipes translation* only has the Beast chastely asking Beauty to marry him.

However, throughout the French version, the verb used is "coucher," to sleep with, not marry. I was surprised at this, but I guess a lot of it could do with context. Would it be implied at the time and in Villeneuve's culture that marriage went hand in hand with a request to have sex? Could it possibly mean only the literal meaning of "sleep," without intercourse?

To quote from an older post of mine, from May 2010,

"The difference between marriage and sleeping is quite significant, although we can assume Villeneuve only meant the most innocent form of sleeping. The night of Beauty's acceptance of the Beast's offer, from Dowson's translation:

"However slight was Beauty's impatience to find herself by the side of her most singular mate, she nevertheless got into bed. The lights went out immediately. Beauty could not help fearing that the enormous weight of the Beast's body would crush the bed. She was agreeably astonished to find that the monster placed himself at her side with as much ease and agility as she had herself sprung into bed. Her surprise was even greater still on hearing him begin to snore forthwith; presently his silence convinced her that he was in a profound sleep."

A striking contrast to Jack Zipes' translation. After the fireworks display ends: "the Beast took his leave, and Beauty retired to rest. No sooner was she asleep than her dear Unknown [the Beast in Prince form, who visits her each night in her dreams] paid her his customary visit."

This is not just difference in how to translate a certain word or phrase. Either Dowson invented several lines about the Beast sleeping on the same bed as Beauty, or Zipes invented the part about the Beast taking his leave and just left the rest out.

So here's what the French actually reads:

"Ce charmant spectacle ayant suffisamment dure, la Bete temoigna a sa nouvelle epouse qu'il etait temps de se mettre au lit. Quelque peu d'impatience qu'eut la Belle de se trouver aupres de cet epoux singulier, elle se coucha. Les lumieres s'eteignirent a l'instant. La Bete, s'approchant, fit apprehender a la Belle que de poids de son corps elle n'ecrasat leur couche. Mais elle fut agreablement etonnee en sentant que ce monstre se mattait a ses cotes aussi legerement qu'elle venait dele faire. Sa surprise fut bien plus grande, quand elle l'entendit ronfler presque aussitot, et que par sa tranquillite, elle eut une preuve certaine qu'il dormait d'un profond sommeil."

And here's a (very) bad online translation, which you can see is very close to the Dowson*, NOT the Zipes translation:

"This charming show having sufficiently hard, the Animal testified has its new wife that it was time to put itself at the bed. Somewhat of impatience which the Beautiful one had to be near this singular husband, it lay down. The lights died out has the moment. The Animal, approaching, made apprehend has the Beautiful one that weight of its body it ecrasat their layer. But it was agreeably etonnee by feeling that this monster was subdued has its dimensions as slightly as it had just done it. Its surprise was much larger, when she intended it to whirr almost at once, and that by her peace, she had an unquestionable proof which he slept of a deep sleep."

I was very surprised. I had assumed Zipes, a more current a respected scholar, would have a more accurate translation. However, from skimming the rest of the French, (again, remember my French is pretty poor,) most of it seemed to be very similar to the Zipes version I'm familiar with.

*To see the sources for each translation, click through to this post.

Illustrations anonymous, done for Charles Lamb's poem, from Surlalune

However, throughout the French version, the verb used is "coucher," to sleep with, not marry. I was surprised at this, but I guess a lot of it could do with context. Would it be implied at the time and in Villeneuve's culture that marriage went hand in hand with a request to have sex? Could it possibly mean only the literal meaning of "sleep," without intercourse?

To quote from an older post of mine, from May 2010,

"The difference between marriage and sleeping is quite significant, although we can assume Villeneuve only meant the most innocent form of sleeping. The night of Beauty's acceptance of the Beast's offer, from Dowson's translation:

"However slight was Beauty's impatience to find herself by the side of her most singular mate, she nevertheless got into bed. The lights went out immediately. Beauty could not help fearing that the enormous weight of the Beast's body would crush the bed. She was agreeably astonished to find that the monster placed himself at her side with as much ease and agility as she had herself sprung into bed. Her surprise was even greater still on hearing him begin to snore forthwith; presently his silence convinced her that he was in a profound sleep."

A striking contrast to Jack Zipes' translation. After the fireworks display ends: "the Beast took his leave, and Beauty retired to rest. No sooner was she asleep than her dear Unknown [the Beast in Prince form, who visits her each night in her dreams] paid her his customary visit."

This is not just difference in how to translate a certain word or phrase. Either Dowson invented several lines about the Beast sleeping on the same bed as Beauty, or Zipes invented the part about the Beast taking his leave and just left the rest out.

So here's what the French actually reads:

"Ce charmant spectacle ayant suffisamment dure, la Bete temoigna a sa nouvelle epouse qu'il etait temps de se mettre au lit. Quelque peu d'impatience qu'eut la Belle de se trouver aupres de cet epoux singulier, elle se coucha. Les lumieres s'eteignirent a l'instant. La Bete, s'approchant, fit apprehender a la Belle que de poids de son corps elle n'ecrasat leur couche. Mais elle fut agreablement etonnee en sentant que ce monstre se mattait a ses cotes aussi legerement qu'elle venait dele faire. Sa surprise fut bien plus grande, quand elle l'entendit ronfler presque aussitot, et que par sa tranquillite, elle eut une preuve certaine qu'il dormait d'un profond sommeil."

And here's a (very) bad online translation, which you can see is very close to the Dowson*, NOT the Zipes translation:

"This charming show having sufficiently hard, the Animal testified has its new wife that it was time to put itself at the bed. Somewhat of impatience which the Beautiful one had to be near this singular husband, it lay down. The lights died out has the moment. The Animal, approaching, made apprehend has the Beautiful one that weight of its body it ecrasat their layer. But it was agreeably etonnee by feeling that this monster was subdued has its dimensions as slightly as it had just done it. Its surprise was much larger, when she intended it to whirr almost at once, and that by her peace, she had an unquestionable proof which he slept of a deep sleep."

I was very surprised. I had assumed Zipes, a more current a respected scholar, would have a more accurate translation. However, from skimming the rest of the French, (again, remember my French is pretty poor,) most of it seemed to be very similar to the Zipes version I'm familiar with.

*To see the sources for each translation, click through to this post.

Illustrations anonymous, done for Charles Lamb's poem, from Surlalune