I'm loving my new book,

Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folklore by Andreas Johns. It came highly recommended by Heidi Anne Heiner, AKA

Surlalune, and Tony was kind enough to get it for me for Christmas!

In the first chapter, "Interpreting Baba Yaga," Johns outlines the history of Baba Yaga scholarship and the different theories about her history and significance. It's kind of amazing to see how many people have attempted to trace the history of her name and origins. "Baba" is a common word, found in all Slavic languages, which primarily means "grandmother," but can also mean "old woman/wife," or "married woman," and can also be used as a derogatory term for a man. In Old Russian the word also had connotations of a midwife, sorceress, or fortune teller.

"Yaga" is much more controversial. There are over 50 variants of Yaga's name, and scholars have attempted to prove that linguistically, the name came from anything from "snake" to "female demon of illness."

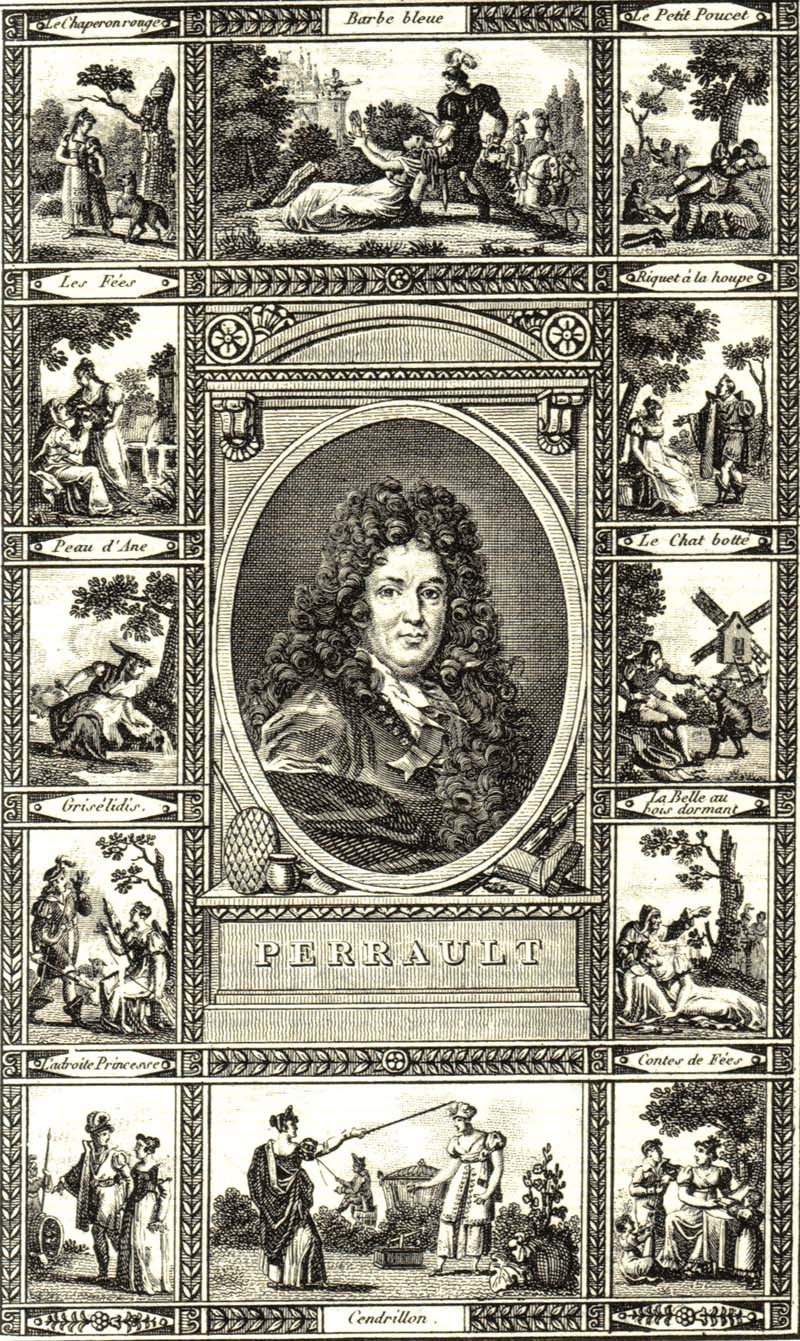

Ivan Bilibin

The name was

not recorded anywhere until 1755, when it was included in a list of Russian folklore characters. In 1780 the author Vasilii Levshin provided an

account of her origin which may or may not be his own invention; the devil cooked twelve nasty women together in a cauldron to capture the essence of evil, and the result was Baba Yaga. Baba Yaga popped up regularly in literature and art after that.

The first attempt at understanding her origins was

mythical; as a diety of the ancient Slavs. Mikhail Chulkov wrote in 1782 that "the Slavs venerated the underworld goddess by this name, representing her as a frightening figure seated in an iron mortar, with an iron pestle in her hands; they made blood sacrifice to her, thinking that she fed it to the two granddaughters they attributed to her, and that she delighted in the shedding of blood herself."

Folklorists such as the famous fairy tale collector Afanasyev believed that

folktales were remnants of old religious beliefs and rites; when the ancient ways were forgotten, the meanings of the stories were also lost and the fairy tales we have are only fragments of these older religions. In attempts to explain the most curious aspects of Baba Yaga, the fact that she can be both a helpful donor as well as an evil, cannibalistic witch, Afanasyev saw her as

represinting a storm cloud. Such a thing would be a welcome relief in summer, a necessity for life, yet could also be treacherous and deadly in the long Russian winters.

Other mythological interpretations of Baba Yaga see her as representing the loss of children's teeth, the crow, the fox, a Bird Goddess, death, feminity, and fertility. For a while it was also popular to see fairy tales as the result of

solar myths, and in 1973 a theory was made that she represents the moon; the waning crescent moon is the explanation for her cannibalistic urges.

Some scholars looked to

historical customs to explain Baba Yaga, such as folklorist Vladimir Propp, who created the system of analyzing fairy tales in terms of the functions they all share. Propp traced Baba Yaga tales back to

old rituals of initiation in which initiates underwent symbolic death and renewal. Yet, although Propp cites rituals from all over the world, he doesn't explain how those customs came to be represented in a Slavic figure. Although his logic is questionable, Propp's work became very influential in subsequent Baba Yaga scholarship, and many writers associated her with death and rebirth.

One very interesting observation was made by Olga Perianez-Chavernoff in 1983; the differences in how Baba Yaga relates to the hero (as villain or donor/helper) has everything to do with the age of the hero.

To young children, Yaga is a threat; she abducts them and attempts to cook and eat them.

Yet when the heroes are adolescents, she is usually the donor-even if she tries to take advantage of them, the older heroes find ways to manipulate her into giving them advice or magical aid in their journey.

Some people interpret

Baba Yaga as being a Mother figure. She is sometimes the mother-in-law or somehow related to the hero; even when she is not, she may represent people's resentments against their mother's control in childhood. In European tales, it is often supposed that the evil stepmother or witch is a manifestation of the "bad" side of the mother, through the eyes of the child-the one who controls and punishes, whereas the "good" mother is often represented in another form, like a magical animal. So in Baba Yaga, the two sides are present in one figure; but why is she split in Europe and not in Russia?

\

Dave Crosland

Jack Zipes sees the tales from a social perspective; Yaga represents the evil rulers who suppress the people. But Johns points out that many Russian tales are obviously aimed at the government and don't disguise their feelings, so why would there be a need for a hidden meaning in Baba Yaga?

Other people have seen Baba Yaga as the result of

gender issues. Yaga, they claim (without evidence) was more benevolent and likely to be good back in the old days of matriarchy; then in the struggle in which patriarchy overcame, she took on more evil traits.

Of course,

Freudian scholars see everything in terms of phallic images. It's actually funny to see how they can take even a single old woman with exaggerated deformities and turn her into something that supposedly represents the act of heterosexual intercourse.

Especially after reading all of these theories together, it becomes obvious that

no one can claim to know the one true meaning of any fairy tale or history (many of these same arguments have been made to interpret the classic fairy tales of Western tradition.) After a while I even started thinking, "do these people actually realize that Baba Yaga is a character and not real?" Although her unique traits, especially her ambiguous moral status, deserve some looking into, it seems odd that scholars try to reconcile all of her characteristics from all of her tales in one master explanation, when in reality, these stories were mostly told by storytellers who only knew the Baba Yaga tales in their region, where they each developed characteristics of their own.

The mere fact that some variants of tales feature Baba Yaga wheras other variants feature a witch would indicate that, while she is a reoccurring staple of folklore,

she is clearly interchangeable with other witches or donors. In Russian folklore, a majority of male heroes are named "Ivan," yet no one is trying to figure out how Ivan could have done every act he is attributed in every Russian fairy tale.

Again, being the only character that goes back and forth between good and evil is significant, sometimes within the same tale. But Yaga is only a helpful character in about 1/3 of her stories, and even there, she is usually an unwilling helper.

To me that doesn't indicate moral ambiguity, but that the hero is sometimes more powerful than her and able to trick her. The actions of Baba Yaga may just reflect the character of the hero-either their goodness, wit, or power. Baba Yaga is fearsome and cruel, but the characters are not helpless against her

-evil can be conquered.

The rest of the book should definitely shed more light on this intriguing character!