I love Megan Kearney's impressively concise summary of the history of the relationship development between Beauty and the Beast over time! Read her whole reply here, summary below:

"So, in trying to sum up, traditionally Beauty and the Beast has been a story about a young woman’s journey to accepting an unconventional male partner. In the twentieth century, it become a popular metaphor for the awakening of female sexuality and power. Now, more and more, we see it as a metaphor for the channeling of negative masculinity into positive masculinity. The story evolves. We pull new meaning from it, stretch it this way and that, examine it in the mirror, and take it apart to see how it ticks. It changes to suit our cultural needs, and it will continue to change."

Art by David Sala

Saturday, January 28, 2017

Wednesday, January 25, 2017

From the Archives: Beauty and the Beast as a Socio-Historical Tale

One of Jerry Griswold's purposes in The Meanings of Beauty and the Beast: A Handbook is to outline the major interpretations critics have assigned to the tale. He divides them into the following categories: psychological, socio-historical, and feminist (which, ironically, includes two very opposite interpretations: those who see the story as victimizing women, and those who find it to be very empowering to women). I've posted before on the psychological as well as the various feministic interpretations, and if you do any type of digging into Beauty and the Beast you're bound to come across them, but I don't think I've ever read about this particular aspect of the tale before, so I was intrigued:

According to Jack Zipes, if we look at the story in its historical context, we will see that it is a story of class struggle. The very presence of a merchant is unusual in the history of fairy tales, which usually feature the poorest of peasants and the most elite royals, but in this story we see the emergence of a middle class.

At the time that de Villeneuve and Beaumont were penning what would become the most famous version of one of the most classic and popular tales (18th century France), the middle class was gaining the upper hand. The members of nobility were increasingly getting poorer, but at least had their status; while the middle class were becoming richer through their businesses. It was a common thing to see a merchant's daughter entering into an arranged marriage with a destitute nobleman, allowing one family to contain both a title and wealth at the same time.

The story of Beauty and the Beast certainly explores the rise and fall of Beauty's family in society-her father starts out as a wealthy merchant, her sisters as materialistic and greedy and always wanting to improve their situation. When Beauty's father loses his money, we are reminded that status based on wealth is not always secure, and the family becomes poor farmers, where it is Beauty's contentedly cheerful, hard-working nature that keeps the family afloat.

Then we meet the Beast-although Beauty has the upper hand in looks, he certainly has the upper hand in wealth, status, and material goods. We of course later find out that he is a prince.

This was actually the opposite kind of situation that was really happening all over France. In this story we have a nobleman whose wealth is supplied by magic and therefore cannot run out, who is generous to the poor family of Beauty-a family who you could argue has been chided for being social climbers and encouraged to become simple, hard-working farmers. According to Griswold, "In other words, in the midst of changing times, Beaumont seems to offer a kind of backwards-looking endorsement of the nobility, a flattering and conservative portrait of the ancien regime." In Zipes' words, the aim of Beaumont is to "put the bourgeoisie in their place."

This was actually the opposite kind of situation that was really happening all over France. In this story we have a nobleman whose wealth is supplied by magic and therefore cannot run out, who is generous to the poor family of Beauty-a family who you could argue has been chided for being social climbers and encouraged to become simple, hard-working farmers. According to Griswold, "In other words, in the midst of changing times, Beaumont seems to offer a kind of backwards-looking endorsement of the nobility, a flattering and conservative portrait of the ancien regime." In Zipes' words, the aim of Beaumont is to "put the bourgeoisie in their place."

This is where I don't understand why scholars refer only to Beaumont's version. Beaumont did not add anything essential to the tale, she only simplified Villeneuve's. The negative portrayal of the materialistic sisters, the fall in status of the family, were all originally Villeneuve's. But when I read the Villeneuve version, it seems to me that the message is to clearly poke fun at strict class boundaries, since each of the characters seem to change status in relationship to each other multiple times, and there is a very clear moral near the end where the good fairy is trying to convince the Queen (the Beast's mother) that Beauty is a worthy bride for her son because of her character, NOT her status (before finally unveiling the truth of Beauty's true identity, being a fairy Princess, therefore pacifying the Queen). So ultimately, Villeneuve's original story probably wasn't pushing for the merchant class to go "back to the farm and become once again hardworking and uncomplaining peasants" as Griswold indicates was Beaumont's goal. (Plus, wasn't Beaumont a member of the middle class herself? She ended up as a governess, probably employed by merchant class families-if they all went back to the farm she wouldn't have had a job or the ability to write fairy tales on the side).

And of course there's the irony present in many fairy tales that, while Beauty is praised for being content as a hardworking peasant, she is the one who is rewarded with unimaginable wealth and no more need for working for the rest of her life. Yet another example where I think the actual events of the tale, mixed with the reader's own natural desires, end up being a much stronger message than the supposed "moral", if that was even what Beaumont was trying to portray.

Illustrations by Eleanor Vere Boyle

According to Jack Zipes, if we look at the story in its historical context, we will see that it is a story of class struggle. The very presence of a merchant is unusual in the history of fairy tales, which usually feature the poorest of peasants and the most elite royals, but in this story we see the emergence of a middle class.

At the time that de Villeneuve and Beaumont were penning what would become the most famous version of one of the most classic and popular tales (18th century France), the middle class was gaining the upper hand. The members of nobility were increasingly getting poorer, but at least had their status; while the middle class were becoming richer through their businesses. It was a common thing to see a merchant's daughter entering into an arranged marriage with a destitute nobleman, allowing one family to contain both a title and wealth at the same time.

The story of Beauty and the Beast certainly explores the rise and fall of Beauty's family in society-her father starts out as a wealthy merchant, her sisters as materialistic and greedy and always wanting to improve their situation. When Beauty's father loses his money, we are reminded that status based on wealth is not always secure, and the family becomes poor farmers, where it is Beauty's contentedly cheerful, hard-working nature that keeps the family afloat.

Then we meet the Beast-although Beauty has the upper hand in looks, he certainly has the upper hand in wealth, status, and material goods. We of course later find out that he is a prince.

This was actually the opposite kind of situation that was really happening all over France. In this story we have a nobleman whose wealth is supplied by magic and therefore cannot run out, who is generous to the poor family of Beauty-a family who you could argue has been chided for being social climbers and encouraged to become simple, hard-working farmers. According to Griswold, "In other words, in the midst of changing times, Beaumont seems to offer a kind of backwards-looking endorsement of the nobility, a flattering and conservative portrait of the ancien regime." In Zipes' words, the aim of Beaumont is to "put the bourgeoisie in their place."

This was actually the opposite kind of situation that was really happening all over France. In this story we have a nobleman whose wealth is supplied by magic and therefore cannot run out, who is generous to the poor family of Beauty-a family who you could argue has been chided for being social climbers and encouraged to become simple, hard-working farmers. According to Griswold, "In other words, in the midst of changing times, Beaumont seems to offer a kind of backwards-looking endorsement of the nobility, a flattering and conservative portrait of the ancien regime." In Zipes' words, the aim of Beaumont is to "put the bourgeoisie in their place."This is where I don't understand why scholars refer only to Beaumont's version. Beaumont did not add anything essential to the tale, she only simplified Villeneuve's. The negative portrayal of the materialistic sisters, the fall in status of the family, were all originally Villeneuve's. But when I read the Villeneuve version, it seems to me that the message is to clearly poke fun at strict class boundaries, since each of the characters seem to change status in relationship to each other multiple times, and there is a very clear moral near the end where the good fairy is trying to convince the Queen (the Beast's mother) that Beauty is a worthy bride for her son because of her character, NOT her status (before finally unveiling the truth of Beauty's true identity, being a fairy Princess, therefore pacifying the Queen). So ultimately, Villeneuve's original story probably wasn't pushing for the merchant class to go "back to the farm and become once again hardworking and uncomplaining peasants" as Griswold indicates was Beaumont's goal. (Plus, wasn't Beaumont a member of the middle class herself? She ended up as a governess, probably employed by merchant class families-if they all went back to the farm she wouldn't have had a job or the ability to write fairy tales on the side).

And of course there's the irony present in many fairy tales that, while Beauty is praised for being content as a hardworking peasant, she is the one who is rewarded with unimaginable wealth and no more need for working for the rest of her life. Yet another example where I think the actual events of the tale, mixed with the reader's own natural desires, end up being a much stronger message than the supposed "moral", if that was even what Beaumont was trying to portray.

Illustrations by Eleanor Vere Boyle

Tuesday, January 17, 2017

Fairy Tale Fashion: The Snow Queen

One more post from Colleen Hill's Fairy Tale Fashion!

In her essay on Andersen's "The Snow Queen," Hill informs us that the fairy tale was initially conceived as a short, ballad-style poem about a young woman and her lover, a poor boy who was abducted by the Snow Queen. The Snow Queen was then more of a sexual predator. The story evolved into the tale we know today, of two children separated when the boy, Kay, gets a piece of an evil mirror lodged in his eye that turns him into a cruel boy who mocks the things he used to love and follows the Snow Queen to her ice palace.

The tale uses opposing imagery-the natural, warm beauty of the rose verses the stark symmetry of mirrors and ice/snowflakes. The mirror in this tale is unusual in that, while mirrors usually tell the truth (such as the mirror in "Snow White" that is bold enough to bluntly tell the Queen when there is someone more beautiful than she), this mirror is deceptive-it distorts reality, causing beautiful things to seem ugly. (In fact, I sometimes thought of this mirror when I was in my first trimester-when foods I usually loved became disgusting to me and activities I enjoyed lost interest for me because of the constant nausea-I felt like I could relate to Kay).

Mirrors usually represent vanity in stories. The theme of vanity is also developed in "Snow Queen" by the reference to Gerda's red shoes. When she goes to search for Kay, she intentionally puts on her new red shoes that Kay has never seen before, but when she goes to the river she is willing to sacrifice her prized possessions to gain information about his whereabouts (but the shoes are returned to her because the river does not know where he is). Interestingly, this tale was written just four months before Anderson wrote the infamous tale "Red Shoes" in which the desire for the colored footwear is completely and repeatedly seen as selfish.

Hill interprets the red shoes as objects of pride, even for Gerda-saying that by wearing them she was initially hoping to impress Kay, but the difference between Gerda and Karen from "Red Shoes" was that Gerda was willing to give up her shoes. This may be, especially given Anderson's feelings about red sheos, but I didn't necessarily read it that way in "Snow Queen." It's natural for a child to be excited to show her friend a new toy or possession, without necessarily trying to impress or show off to your friend. If Gerda had taken a beautiful red rose and tucked it behind her ear with the intention of showing Kay, would that be interpreted as vanity? The rose would still be beautiful and displayed on Gerda, but fairy tale characters who request roses rather than clothes and jewelry are held up as the example of being non-materialistic, like Beauty in "Beauty and the Beast." Yet roses are a symbol of her friendship with Kay-when staying with the old woman, it was seeing an image of a rose that reminded Gerda of her quest to find Kay. Could the wearing of the red shoes even have been Gerda's attempt to remind Kay of their beloved roses, since a real rose wouldn't survive a long journey? The colorful roses of Kay and Gerda's childhood playdates are a stark contrast to the colorless white of the Snow Queen's palace.

Hill interprets the red shoes as objects of pride, even for Gerda-saying that by wearing them she was initially hoping to impress Kay, but the difference between Gerda and Karen from "Red Shoes" was that Gerda was willing to give up her shoes. This may be, especially given Anderson's feelings about red sheos, but I didn't necessarily read it that way in "Snow Queen." It's natural for a child to be excited to show her friend a new toy or possession, without necessarily trying to impress or show off to your friend. If Gerda had taken a beautiful red rose and tucked it behind her ear with the intention of showing Kay, would that be interpreted as vanity? The rose would still be beautiful and displayed on Gerda, but fairy tale characters who request roses rather than clothes and jewelry are held up as the example of being non-materialistic, like Beauty in "Beauty and the Beast." Yet roses are a symbol of her friendship with Kay-when staying with the old woman, it was seeing an image of a rose that reminded Gerda of her quest to find Kay. Could the wearing of the red shoes even have been Gerda's attempt to remind Kay of their beloved roses, since a real rose wouldn't survive a long journey? The colorful roses of Kay and Gerda's childhood playdates are a stark contrast to the colorless white of the Snow Queen's palace.

Red Morocco leather shoes, from 1800-1810

Although, it was more of a natural assumption at the time to associate red shoes with luxury, since red dye was more difficult to produce, and therefore more expensive, so red was a color only the wealthier could afford. But it seems that illustrators to tend to intentionally bring out the contrast in warm colors associated with Gerda, her friendship with Kay, and her journey to find him, as opposed to the cold realm of the Snow Queen. See Arthur Rackham's illustration of Kay and Gerda in their garden, and Edmund Dulac's image of Gerda at the old woman's house:

Compared with the Snow Queen/her palace by the same illustrators:

Although, I may be too quick to defend the wearing of red, just based on our own modern culture, where bright colors are just as easily accessed as neutrals. If anything, we tend to associate good things with characters who wear bright colors, aligning them with bright, joyful personalities. What do you see as the significance of Gerda's red shoes?

In her essay on Andersen's "The Snow Queen," Hill informs us that the fairy tale was initially conceived as a short, ballad-style poem about a young woman and her lover, a poor boy who was abducted by the Snow Queen. The Snow Queen was then more of a sexual predator. The story evolved into the tale we know today, of two children separated when the boy, Kay, gets a piece of an evil mirror lodged in his eye that turns him into a cruel boy who mocks the things he used to love and follows the Snow Queen to her ice palace.

The tale uses opposing imagery-the natural, warm beauty of the rose verses the stark symmetry of mirrors and ice/snowflakes. The mirror in this tale is unusual in that, while mirrors usually tell the truth (such as the mirror in "Snow White" that is bold enough to bluntly tell the Queen when there is someone more beautiful than she), this mirror is deceptive-it distorts reality, causing beautiful things to seem ugly. (In fact, I sometimes thought of this mirror when I was in my first trimester-when foods I usually loved became disgusting to me and activities I enjoyed lost interest for me because of the constant nausea-I felt like I could relate to Kay).

Mirrors usually represent vanity in stories. The theme of vanity is also developed in "Snow Queen" by the reference to Gerda's red shoes. When she goes to search for Kay, she intentionally puts on her new red shoes that Kay has never seen before, but when she goes to the river she is willing to sacrifice her prized possessions to gain information about his whereabouts (but the shoes are returned to her because the river does not know where he is). Interestingly, this tale was written just four months before Anderson wrote the infamous tale "Red Shoes" in which the desire for the colored footwear is completely and repeatedly seen as selfish.

From the "Snow Queen" section of the Fairy Tale Fashion exhibit at the Fashion Institute of Technology. Far left; white fur cape by J. Mendel, second to the left; not in the book, second to the right; Alexander McQueen Fall 2008 dress inspired by snowflakes, far right; Tom Ford Spring 2014 dress that imitates shards of a broken mirror

Hill interprets the red shoes as objects of pride, even for Gerda-saying that by wearing them she was initially hoping to impress Kay, but the difference between Gerda and Karen from "Red Shoes" was that Gerda was willing to give up her shoes. This may be, especially given Anderson's feelings about red sheos, but I didn't necessarily read it that way in "Snow Queen." It's natural for a child to be excited to show her friend a new toy or possession, without necessarily trying to impress or show off to your friend. If Gerda had taken a beautiful red rose and tucked it behind her ear with the intention of showing Kay, would that be interpreted as vanity? The rose would still be beautiful and displayed on Gerda, but fairy tale characters who request roses rather than clothes and jewelry are held up as the example of being non-materialistic, like Beauty in "Beauty and the Beast." Yet roses are a symbol of her friendship with Kay-when staying with the old woman, it was seeing an image of a rose that reminded Gerda of her quest to find Kay. Could the wearing of the red shoes even have been Gerda's attempt to remind Kay of their beloved roses, since a real rose wouldn't survive a long journey? The colorful roses of Kay and Gerda's childhood playdates are a stark contrast to the colorless white of the Snow Queen's palace.

Hill interprets the red shoes as objects of pride, even for Gerda-saying that by wearing them she was initially hoping to impress Kay, but the difference between Gerda and Karen from "Red Shoes" was that Gerda was willing to give up her shoes. This may be, especially given Anderson's feelings about red sheos, but I didn't necessarily read it that way in "Snow Queen." It's natural for a child to be excited to show her friend a new toy or possession, without necessarily trying to impress or show off to your friend. If Gerda had taken a beautiful red rose and tucked it behind her ear with the intention of showing Kay, would that be interpreted as vanity? The rose would still be beautiful and displayed on Gerda, but fairy tale characters who request roses rather than clothes and jewelry are held up as the example of being non-materialistic, like Beauty in "Beauty and the Beast." Yet roses are a symbol of her friendship with Kay-when staying with the old woman, it was seeing an image of a rose that reminded Gerda of her quest to find Kay. Could the wearing of the red shoes even have been Gerda's attempt to remind Kay of their beloved roses, since a real rose wouldn't survive a long journey? The colorful roses of Kay and Gerda's childhood playdates are a stark contrast to the colorless white of the Snow Queen's palace.Red Morocco leather shoes, from 1800-1810

Although, it was more of a natural assumption at the time to associate red shoes with luxury, since red dye was more difficult to produce, and therefore more expensive, so red was a color only the wealthier could afford. But it seems that illustrators to tend to intentionally bring out the contrast in warm colors associated with Gerda, her friendship with Kay, and her journey to find him, as opposed to the cold realm of the Snow Queen. See Arthur Rackham's illustration of Kay and Gerda in their garden, and Edmund Dulac's image of Gerda at the old woman's house:

Compared with the Snow Queen/her palace by the same illustrators:

Although, I may be too quick to defend the wearing of red, just based on our own modern culture, where bright colors are just as easily accessed as neutrals. If anything, we tend to associate good things with characters who wear bright colors, aligning them with bright, joyful personalities. What do you see as the significance of Gerda's red shoes?

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

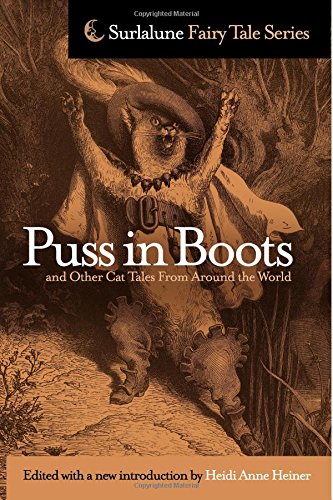

Surlalune's Puss in Boots and Other Cat Tales From Around the World

I always get excited when another Surlalune collection comes out, and I was especially excited that Heidi Anne Heiner was kind enough to send me a copy of her Puss in Boots and Other Cat Tales From Around the World!

I always get excited when another Surlalune collection comes out, and I was especially excited that Heidi Anne Heiner was kind enough to send me a copy of her Puss in Boots and Other Cat Tales From Around the World!"Puss in Boots" is not a tale I'm especially familiar with-in nearly 7 years of blogging (!!) I've only had three other posts with the tag. It's not a tale that scholars frequently like to discuss or artists depict, so it's a great opportunity to learn more about this iconic character and story through essays as well as several different versions from folklore! And the unique thing about this collection is that, even if Puss in Boots isn't your favorite, the other cat tales fall into different tale types, such as "Cat Bride," "The Kind and Unkind Girls," "The Magic Ring," and Witches and Cats (that will be fun for Halloween some year!). Surlalune has been posting about each of the categories over on her blog so you can hop over there to learn more.

I'm slowly reading about the famous Puss in Boots, but I've also been enjoying reading the tales in the "Bremen Town Musicians" section. When I first spotted the title in my book of Grimm tales, I got excited to read a story about musicians because...I'm a musician! Of course I discovered it really has nothing to do with music, but animals making noise, which initially disappointed me. But over the years I've still had an affection for the tale just because of the name, and after reading more versions I'm really coming to appreciate it! The stories really have a great message about not writing off those who are aged or might otherwise be overlooked/seen as useless by society. The idea of a group of misfits banding together and ending up victorious is a pretty common trope in many of our more modern favorite stories.

I'm slowly reading about the famous Puss in Boots, but I've also been enjoying reading the tales in the "Bremen Town Musicians" section. When I first spotted the title in my book of Grimm tales, I got excited to read a story about musicians because...I'm a musician! Of course I discovered it really has nothing to do with music, but animals making noise, which initially disappointed me. But over the years I've still had an affection for the tale just because of the name, and after reading more versions I'm really coming to appreciate it! The stories really have a great message about not writing off those who are aged or might otherwise be overlooked/seen as useless by society. The idea of a group of misfits banding together and ending up victorious is a pretty common trope in many of our more modern favorite stories.In some versions, the way the animals scare off the robbers is more intentional, and other times it's accidental. The former way gives the animals more credit to their intelligence, but the latter is often funnier. One of my favorites is "The Choristers of St. Gudule," in which the donkey who begins the quest believes he has a magnificent voice and should go join the choir in the Cathedral in Brussels. The other animals, a dog, cat, and rooster, are all known for making noise that is unpleasant for humans to hear but each animal is very proud of. When they see the food the robbers are eating, the donkey suggests that they "serenade them, and perhaps they'll throw us something as a reward. Music, you know, has charms to sooth the savage beast." The irony in the tale makes it stand out as being the funniest (in my opinion).

In most of the tales it is robbers that are being scared off, but one of the story notes says that it can sometimes be wolves, therefore making it a story of domestic animals triumphing over wild. But one thing that I find curious these animal is the double standards in animal treatment. In Puss in Boots, the protagonist is rewarded for doing no more than trusting the cat he was given as his inheritance, which was seen as the worst option. This would appear to have the message that, once again, you shouldn't underestimate that which the world may give the least value to. But then the Puss himself keeps going out and killing other animals to present to the King, so not all animal life is given value (maybe...only those that talk, like in Narnia??).

In Bremen Town Musician tales, the old animals who are no longer of use to their masters are the heroes. Yet in the Irish tale "Jack and his Comrades" (sometimes there is a poor boy named Jack in the ragtag group), he asks his mother to kill his rooster for him before he goes out into the world to seek his fortune...only to later save a rooster from a fox that was about to kill him and welcome him into their group! The animals, when they find the robbers, sometimes only see them counting their money, but sometimes see them eating a large meal. Most of the time the food isn't described, but I wonder if those meals would have included meat...in one version from the United States, turkey is listed as one of the delicacies the robbers are eating.

This does highlight the irony that many of us experience who aren't vegetarians and yet sympathize with animal stories, especially those in which they're trying to avoid being eaten. According to this study, only 3.2% of Americans are vegetarians, yet who doesn't root for Babe, or Wilbur in "Charlotte's Web"? There is, of course, a divide between reality and fiction, so it's interesting that the characters within these stories tend to have the same inconsistencies, (which tend to go unnoticed by the readers).

Tuesday, January 3, 2017

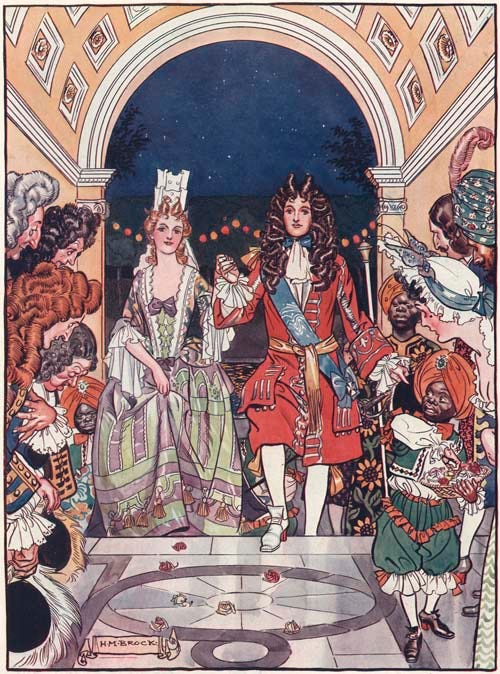

H. M. Brock's Beauty and the Beast

Happy New Year! Hope you were all able to spend some time with friends and family over the winter holidays!

I got a few fairy tale treasures over the last month to share! First up, I received another book to add to my Beauty and the Beast collection, H. M. Brock's 1914 illustrated version. The copy I got has an introduction by Jerry Griswold, author of one of my favorite books on BATB.

I got a few fairy tale treasures over the last month to share! First up, I received another book to add to my Beauty and the Beast collection, H. M. Brock's 1914 illustrated version. The copy I got has an introduction by Jerry Griswold, author of one of my favorite books on BATB.

The prose, adapted by an anonymous writer, follows the traditional French fairy tale pretty faithfully, but with a faster pace than either Beaumont or Villeneuve. One unique aspect I don't think I've read before was that when Beauty wishes herself back with her family, she uses the magic rose. Her sisters try to use the rose for themselves-only as soon as they wish on it, it withers. Beauty is dismayed to find the withered rose on the floor of her sister's room, but as soon as she picks it up, it blooms healthily again.

I wasn't familiar with H. M. Brock's illustrations before. They mimic Walter Crane's 1874 illustrations, but as Griswold discusses in the introduction, Brock has his own unique contributions.

I got a few fairy tale treasures over the last month to share! First up, I received another book to add to my Beauty and the Beast collection, H. M. Brock's 1914 illustrated version. The copy I got has an introduction by Jerry Griswold, author of one of my favorite books on BATB.

I got a few fairy tale treasures over the last month to share! First up, I received another book to add to my Beauty and the Beast collection, H. M. Brock's 1914 illustrated version. The copy I got has an introduction by Jerry Griswold, author of one of my favorite books on BATB.The prose, adapted by an anonymous writer, follows the traditional French fairy tale pretty faithfully, but with a faster pace than either Beaumont or Villeneuve. One unique aspect I don't think I've read before was that when Beauty wishes herself back with her family, she uses the magic rose. Her sisters try to use the rose for themselves-only as soon as they wish on it, it withers. Beauty is dismayed to find the withered rose on the floor of her sister's room, but as soon as she picks it up, it blooms healthily again.

I wasn't familiar with H. M. Brock's illustrations before. They mimic Walter Crane's 1874 illustrations, but as Griswold discusses in the introduction, Brock has his own unique contributions.

Brock's emphasis, Griswold says (other than the luxurious, Cowardly-lion like locks of the Beast) is on the enchanted servants. Beauty's father is waited on by disembodied hands that seem to foreshadow Cocteau's row of candelabra sconces that appear to be disembodied human arms. Beauty's servants aren't as creepy; she gets monkey servants like in Crane (and in Villeneuve's "original" story).

Brock's Disembodied hands wait on Beauty's Father

Disembodied arms hold candelabras in Cocteau's 1946 film

Walter Crane's monkey servants in procession with Beauty

Brock's parallel monkey servant procession