Karen E. Rowe has an essay entitled "To Spin a Yarn: The Female Voice in Folklore and Fairy Tale" that can be found in The Classic Fairy Tales, edited by Maria Tatar (who was just featured in Faerie Magazine). She begins by telling the story of Philomela from Ovid's Metamorphosis.

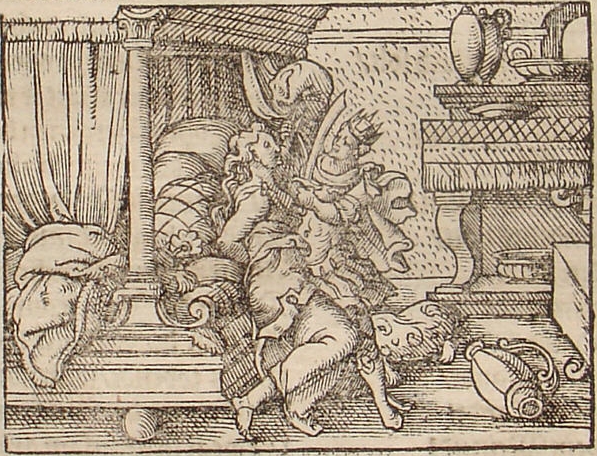

Virgil Solis, 1562

Philomela was raped. When she threatened to expose her attacker, Tereus, he cut out her tongue and kept her imprisoned in the woods. Silenced and confined to the home (sounds like the plight of many women throughout history), she did not give up, but wove an intricate tapestry that told the story of what had happened to her. Through the seemingly harmless, domestic art of weaving, she exposed the truth-her art became her voice. She gave her tapestry to an old woman, who delivered it to the queen, who understood and punished Tereus. Philomela was transformed into a bird, who sings eternally her tale of woe.

Rowe uses this story as a way to demonstrate that women throughout history have used their abilities-specifically for our purposes, storytelling-to be their voices. The story was passed from Philomela to the old woman to the queen-a chain of women who have an intimate connection and common knowledge that is unknown to Tereus.

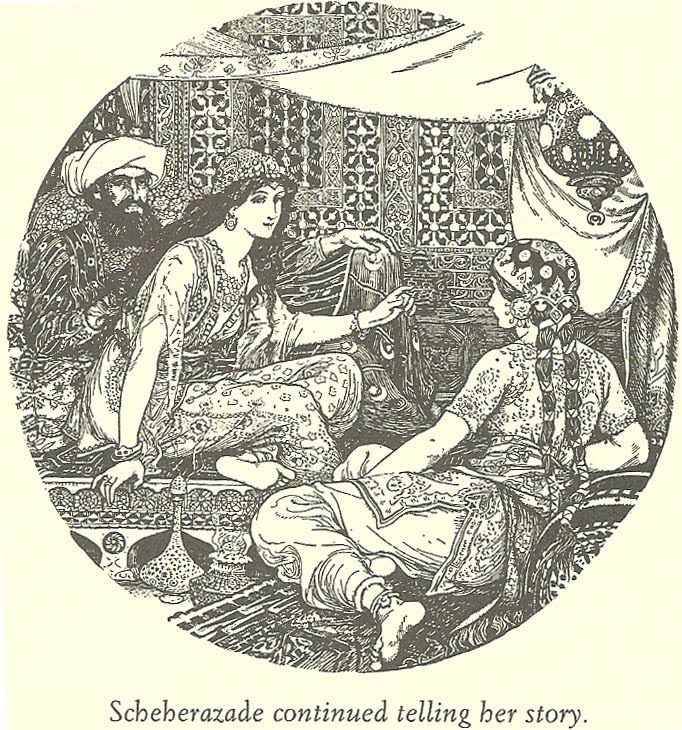

Reader's Digest

Throughout history, storytelling has been seen as a feminine task. Telling stories is not just the ability to recite back a plot, but also to shape each story in a way that applies to the listener and their situation. Rowe reminds us of Scheherezade*, whose storytelling was literally salvation for herself and untold future women in the kingdom of Shahryar. And although most of the world's most famous fairy tale collections were gathered by men-Straparola, Basile, Perrault, the brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen-all of these men claimed to have gotten their tales from women. Although the authors shaped the tales according to their preference, they most likely heard some of the stories in their childhood from their nurses, mothers, etc. Citing young girls or comforting, grandmotherly old women as the tellers of their stories "validated the authenticity of the folk stories."

Jacopo Pontormo

Storytelling would often accompany some of the more mindless tasks that women gathered to do in the evenings, like spinning. With that, and the image of the three (female) fates who spun birth, life, and death of the human race, controlling the threads, we have the phrase "spinning a tale." Sometimes this would have been mere entertainment, but it may also have been, in many cases, a way to "transmit the secret truths of culture itself," to "a sisterhood...who will understand the hidden language."

I wish that, from here, Rowe had gone on to cite specific examples of tales and plot elements that showed this secret communication, but she doesn't. I have some ideas-the horrific plight of Bluebeard's wife may have been a way that women warned each other of the dangers that exist within marriage, just as Animal Bridegroom tales in which daughters are thoughtlessly given to horrible monsters in marriage would have been a way to show the horrors of arranged marriages that betrothed very young girls to older and/or otherwise undesirable men. People wonder about all the cruelty and violence in fairy tales, and it was often just a way of reflecting life. Any other ideas?

*Also-apparently Scheherezade may have a historical predecessor, Princess Homai, daughter of Artaxerxes I. There are also parallels between Scheherezade and the biblical Esther that I hadn't considered before. According to this encyclopedia, many of the stories of the Nights had a historical basis. Interesting to ponder...

Hey, wasn't it a woman who first coined the term "fairy tales" (Les Contes des Fees)? Madame d'Aulnoy, to be specific?

ReplyDeleteAnd then there's Marina Warner's "From the Beast to the Blonde" - a whole fat book about this topic (http://quillandqwerty.wordpress.com/2013/11/07/marina-warner/). From what you're saying of the Rowe essay, it's very much along the same lines.

ReplyDeleteAdamYJ-That is entirely possible, I don't feel like fact checking at the moment but it wouldn't be surprising.

ReplyDeletequillandqwerty-yes!! Such a great book. This essay is kind of like a very boiled down version of the first part of it.