Despite the more common modern interpretation (and when I say "modern" that means the last several hundred years) of LRRH being a cautionary tale about sexual predators, it's likely that the story originated with a more literal intent. In the regions of France where folk LRRH variants were most prevalent, were also the regions where werewolf trials were most common in the medieval age (read more on what I learned about this from Jack Zipes here).

According to four witnesses and "divers others that have seen the same," Stubbe Peeter was a man greatly inclined to evil, so much so that the Devil gave him the ability to transform into a beast. He could become a wolf at will. He had unnatural relations with his own daughter, conceiving a child through her, and took delight in killing that same child once he had grown.

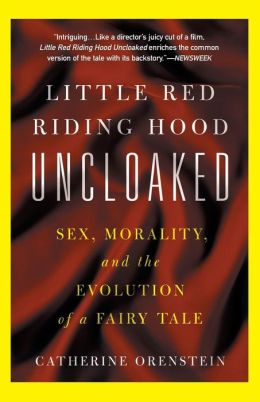

Image from here-artist/source ???

He killed and destroyed numerous other people and livestock. The inhabitants of nearby towns would find limbs of dead women and children scattered among the fields.

In one reported instance, the wolf attacked a little girl. He meant to grab her throat, but because of the clasp of the child's coat around her neck, he could not kill her. By this time other people had come to frighten the wolf away and the child remained alive.

It's that last part that possibly links Stubbe Peeter to the tradition of Little Red Riding Hood tales and not just another werewolf story-the significance of the coat, and the fact that a young girl of all people was able to escape the clutches of the evil wolf.

Amber Kenneson

Wolf attacks were rampant in certain rural areas of Europe, as was the belief in werewolves. The Court of Dole had procedures for a wolf sighting: all the villagers, when they heard the alarm, should gather together at the church, and take note of who did not show up-with the assumption that the one missing was under suspicion. Courts of the 16th century regularly sentenced men to death on the accusation that they were werewolves. Both Orenstein and Zipes list specific names of other men who underwent werewolf trials, but the crazy thing is, the records show that they confessed to the crimes of killing and eating animals, children, and babies.

The fact of their confessions shocked me initially, until I noticed this phrase referring to the unfortunate Gilles Garnier: "confessed without torture." Sadly, fear and not a desire for truth and justice had the power in many courtrooms-men arrested and accused of being a werewolf would be tortured until they confessed (the same went for witch trials and women). Many probably figured, if they were going to be killed either way, they might as well minimize their torture and confess.

Lukas Mayer: Woodcut of the execution of Peter Stumpp

Orenstein also presents a very interesting theory toconsider: in some old English variations of the tale, the wolf is called a "gaffer" wolf, a word that is could simply mean an older person, but was often used to mean a relation. The word may be referring to incest, which was a common accusation at werewolf trials. If we understand the wolf to be Red's own grandfather, this could explain why she seems to have no suspicion and fear when she finds him in her grandmother's bed.

This version is so different from current ideas of LRRH and the wolf it almost makes me angry to scroll through image after image of cute little wolf dolls and toys:

In the words of Catherine Orenstein, "Such spectacles and stories provide a clue to the mental landscape of the past shared by those who told stories on dark winter nights around a fire, with perhaps a wolf or two howling in the background. Fairy tales are far from the reality of the modern reader. But to a sixteenth-century peasant, such plots took place just outside the door. 'Little Red Riding Hood' was not a frivolous fable but a direct warning from a true story. Her villain was real-maybe even a neighbor."

Fascinating post! I recently studied 'Little Red Riding Hood' for a class at university, but looking more at its sexual implications that social history so I didn't know much about Peter Stumpp or werewolf trials. I've read much about women being trialed for witchcraft, but it seems that men didn't escape persecution, either. I often wonder what it would be like to have lived back then, when, as Orenstein put it, 'such plots took place just outside the door.' It certainly gives you a new perspective to look at fairy tales from.

ReplyDeleteGlad you find it interesting too! There's just so much to consider when trying to determine what fairy tales "mean," for each culture, and then for each individual...

DeleteI did a whole project on werewolf superstitions in high school (I was a big classic monsters geek even before I was a fairy tale geek). I remember reading all sorts of stuff about werewolf trials and the various signs that someone was a werewolf. Some cultures even used to believe that anyone who was a werewolf in life would become a vampire after death.

ReplyDeleteI had never done research into werewolves before, but I had read up a bit on vampires-wasn't aware they were connected at all! There's definitely similarities between the two superstitions

Delete