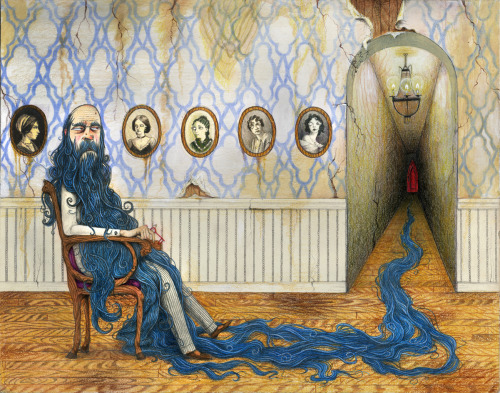

(heads of children!! even creepier!)

But one thing I really never consider is the fact that Bluebeard can actually be seen as a feminist tale. We normally think the opposite-since Perrault added that moral about the perils of women's curiosity, whether he was being sarcastic or not, the general consensus for a long time afterwards was that women's curiosity was the real warning of the story. This fitted in perfectly with the view long held that knowledgeable and powerful women were dangerous.

Yet we know that folkloric versions of the tale did not condemn the woman for her curiosity at all. In fact, in some versions, she ends up rescuing the previously murdered women, bringing them back to life, and/or killing the Bluebeard character (see Grimms' "Fitcher's Bird" for an example). In fact, many actual folk tales are really not so misogynist as many now think-Maria Tatar says, "The gendered division [of active males and passive females]...was also not as rigorously enforced in folktales as in myths. If we look, for example, at some of the tales from the Brothers Grimm that did not make it into our fairy-tale canon, we find that there are many male Cinderellas who suffer in silence and many active women who undertake journeys and carry out tasks to disenchant bridegrooms" (emphasis mine). The separation of men's and women's roles into the now upsetting stereotype was a cultural process that was enforced throughout the Victorian era.

Nora Aoyagi

Tatar points out several reasons why even Perrault's curious wife is actually not as passive as we imagine.

1. The heroine's discovery of her husband's secret

Although the curiosity aspect was shamed at the time, few could really imagine that a happy ending could have resulted by the wife's remaining ignorantly married to a murderer. Her search for knowledge, although exaggerated and mocked, in many Victorian versions, makes her the detective of the story.

This is especially interesting in light of the fact that the detective novel was just becoming a genre and became immensely popular in the later Victorian era. Sherlock Holmes used logic and observations to attain justice for murderers; Bluebeard's wife was doing the same thing before he came along (because it's a little strange for a husband to keep a whole room of his house off limits to his own wife-that alone should elicit suspicion).

And, as Tatar also reminds us, the idea of a woman acquiring knowledge to gain power over the man she is indebted to is also an element of the fairy tale Rumpelstiltskin-and interestingly that heroine is typically seen as the hero and the strange little man the villain.

2. Bluebeard's wife cleverly stalls her own death

A completely passive character would have just submitted to her own fate, but the heroine in this story makes up all kinds of excuses to prolong her death. Perrault's heroine asks to say her prayers. Some critics say that this shows her being piously repentant for her "sin" but it could be a clever way of stalling (because even the most religious would hardly consider death a fitting punishment for curiosity!). Folkloric versions may have her insisting on donning bridal wear first; others put on articles of clothing one by one, in sort of a reverse image of Little Red Riding Hood's taking off her clothes in the old French version.

3. The heroine engineers her own rescue

This one is definitely better seen in folkloric versions than Perrault; the older characters sent out magical animals with messages for her family. As mentioned above, some heroines would resurrect the dead bodies, which were sometimes her sisters, and the heroine herself would kill the murderous husband. Perrault's unfortunate wife sends her sister up to watch for her brothers, which is not quite as active a role, but still shows that she has thought of a way to call for help as quickly as possible and took initiative when some might have just given up hope.

Bluebeard's Wives

4. The story has a non-traditional ending

The traditional fairy tale formula begins with a young person who lives with their family and ends with them married. Critics don't like the idea that you're not complete without a romantic relationship, but this progression can also be seen as symbolic of a person who grows up, leaves their childhood family, and starts their own.

Yet in this fairy tale, the heroine starts in a married relationship, and ends up alone in the happy ending, having gotten rid of her husband with the help of her family. She is now the master of Bluebeard's grand estate and generally puts the vast wealth to charitable use. She goes from powerless to powerful; dependent to independent.

In Perrault she gets herself a new, "worthy" husband...so while she may not be a single woman, she still shows she has power in her ability to get her own spouse now. (In fact, the wording there, about how she got herself a "worthy husband who made her forget the ill time she had passed with Bluebeard" really reveals, I think, that Perrault did not actually view the wife as the transgressor). In "Fitcher's Bird," it is never said what she does afterwards-her eventual fate is left up to our imaginations.

"Widower Bluebeard and the Red Key"

* Information from Secrets Beyond the Door by Maria Tatar

Bluebeard bonus link: Check out this article from 1869 from Lippincott's Magazine in which someone (uncredited author) makes the argument that Bluebeard was a victim of circumstances and the wife made everything up to get his money. Aside from the disturbing fact that this is once again blaming the female, the article does have some interesting points, although the writer doesn't seem to be able to separate some elements of the fairy tale genre from real life. But here's an excerpt:

"Strangely enough, she deserts her company and goes up alone (mark that), opens the door, drops the key in her fright, and sees—what? The gory corpses of his former wives suspended by the hair of their heads! Now let me ask, in the name of common sense, how did she know they were his wives? How was she able to recognize them after such a lapse of time? Why did she not cry out and bring up the company from below? or why did she not run away and escape from the vengeance of the abominable tyrant? But no: she carefully picks up the key, and fruitlessly endeavors to brighten it with ashes or Sand-paper. When her husband unexpectedly returns the next morning, she hands him the keys as though nothing had happened."

It is often overlooked that Perraults tale has two morals. One is directed at women, warning them against curiosity, the other is directed at men: Perrault states that obviously the story took place *long* ago and that no man today would treat his wife poorly... and while it can be argued whether or not the first moral is meant ironically, the second is clearly dripping with sarcasm. Perraults shames men for treating their wves cruelly by making clear that such behaviour fits into the barbarous times of the "Dark Ages" and not into modern life.

ReplyDeleteThat is definitely true, although I even wonder how that second moral would have gone across in Perrault's time. While abusing wives was more commonplace, outright killing of them was definitely frowned upon, so I wonder if even awful husbands would have missed that it was directed at them...But as I think Tatar also points out, the second moral also asserts that "the wife of today will let him know who the master is," implying that women were domineering over their husbands, which is how misogynists tend to interpret women gaining basic rights. I wish I could learn about how people at the time reacted to Perrault's morals because there's so many ways to interpret them and I only have a vague understanding of the culture

DeleteI recall a very strange Irish version of this tale - wish I could remember the title. I found it in a collection of Celtic folk tales whose title I've also forgotten.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, in it, the young wife befriends some animals with which she shares a meal - a familiar fairytale trope - and in return, they help her to clean the bloodstained key. Now, here's where it becomes strange. The husband returns, sees the clean key and says, "Oh, well done, you obeyed me!" and the woman and her serial killer husband live happily ever after! Weird indeed!

I think I remember you shared this on another post on Bluebeard! Such a strange and unsatisfying ending, and thankfully it's rare to see a version that ends like this.

DeleteI blame Perrault and the Victorian times for making the heroine passive and weak. And we know for a fact the older versions of the tale had the heroines proactive and cunning. I remember reading an old version of Bluebeard about a maiden who wanted to be with her fiance for the night but her parents refused it, except for her priest who gave her permission. When she went into the woods, she finds him digging a hole, sees other gravestones next to it and asks what's it about. Its then revealed that the fiance is a rapist who would kill his lovers with an axe if they do not sleep with him. The heroine pretends to agree with this, so long as the man undresses first. As soon as his back was turned to undress, the heroine quickly grabs the axe and chops his head off. The ending as her returning home as hero (and other versions said she even killed his evil family).

ReplyDeleteThat's definitely true about the Victorian era changing female heroines into being more passive, although with Perrault, from everything I've read it seems he really was being satirical, although his tales can still be quite upsetting to read and a disturbing amount of people seemed to take them literally.

DeleteBut what a fascinating version! And what a powerful statement about date rape...I've never heard that story before!

This comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteIf you're fascinated by the story, read Angela Carter's "Bloody Chamber" version of it

ReplyDeleteYes that's a good one...but it's been a few years and I'm due for a reread of Bloody Chamber!

Delete